Discover how to write a children’s book that captures hearts and sparks imaginations. From idea to final page, this playful guide offers clear steps, creative tips, and answers to all your biggest questions.

Introduction: Why Writing for Children Is a Unique Craft

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before:

“Oh, you’re writing a children’s book? That must be easy. What is it, like… 500 words?”

If only.

Writing for children isn’t easy. It’s precise. Ruthlessly so. You have to distil wonder, emotion, and story into a space no bigger than a page of toast. You’re not just writing at kids, you’re writing for them. And if you’ve ever read to a group of five-year-olds who are sugar-rushed and wiggly, you’ll know one thing: if your story doesn’t grip them instantly, it’s game over.

But when you get it right? Magic. Kids don’t fake their emotions. If they lean in, eyes wide, mouths open, you’ve done it. You’ve built a bridge between your words and their wild, brilliant little minds.

And that’s the goal here: not just to give you tips for writing a children’s book, but to help you write one that works. One that fits the child it was meant for like a favorite blanket. One that respects their intelligence, fuels their imagination, and maybe even makes them braver.

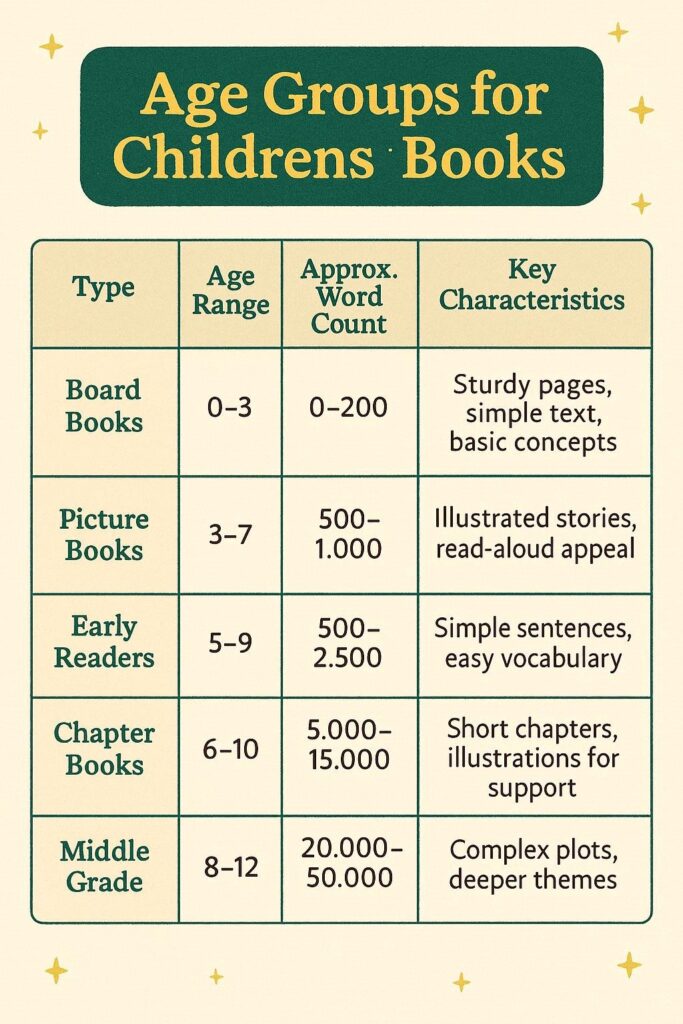

Know Your Target Age Group

One of the most common missteps in writing a children’s book is treating “kids” like one big, uniform group. But a two-year-old and a ten-year-old don’t just read differently, they think, speak, and feel differently too.

If you want to write a story that lands, you have to get specific. Tailor your language, themes, structure, and tone to the age you’re writing for. Let’s break it down by age group so you know exactly what to aim for.

Ages 0–3: Board Books

Keep it short, under 300 words. These books are all about sound, color, and rhythm. Think: animal noises, big bold illustrations, repetitive language. You’re not telling a story so much as inviting a sensory experience.

Themes? Simple and joyful. Animals, family, bedtime, shapes. The goal here is delight and familiarity.

Ages 3–6: Picture Books

Now you’re telling actual stories, but still with minimal words, somewhere between 300 and 800. These readers crave imagination and emotional resonance. They want to see the world from a new angle but also recognize themselves in it.

Play with repetition, surprise, and humor. Common themes include feelings, problem-solving, wonder, and friendship.

Ages 6–9: Early Readers

These kids are beginning to read on their own, so your writing needs to support and encourage that. Expect to write 800 to 2,000 words, with short chapters and clear sentence structure.

Characters should show growth, explore new ideas, and take small risks. These stories are often about confidence-building, independence, and learning how the world works.

Ages 8–12: Middle Grade Novels

This is where writing children’s books stretches into real storytelling territory, word counts go up (15,000 to 50,000+), and so does complexity. Themes can be deeper: identity, friendship, conflict, fear, loyalty, injustice. These readers want characters who feel real, stakes that matter, and emotional arcs that don’t talk down to them. The best middle grade books leave kids feeling seen and challenged in the same breath.

Knowing who you’re writing for isn’t a suggestion, it’s the groundwork. Nail this part, and your story has a shot at actually sticking with the kids it’s meant for.

If youre looking for children’s book writing services, feel free to get in touch.

Brainstorm Ideas That Spark Wonder

Let’s get something out of the way: you don’t need to have kids to write for them. But you do need to remember what it felt like to be one.

The best children’s stories don’t come from trying to “teach a lesson.” They come from questions. Big, open, magical questions like:

What if the moon went missing?

What if a girl could talk to trees?

What if your shadow had a secret life of its own?

If you’re wondering how to write children’s books that truly land, start there. With curiosity. With wonder. With emotional truth.

Watch and Listen to Real Kids

If you have the chance to be around children, listen. Really listen. What makes them light up? What makes them cry, ask weird questions, or suddenly go quiet?

You’re not writing about children. You’re writing as if you are one, seeing the world sideways, with all its strangeness and magic still intact.

Dig Into Your Own Childhood

What scared you? What made you feel brave? Who hurt you? Who made you laugh until your stomach ached? What was the one thing you wanted that you couldn’t have?

Write from there. Kids can smell emotional honesty a mile away. If the feelings are real, they’ll lean in.

Keep an Idea Notebook

Inspiration doesn’t always strike when you’re at your desk. Sometimes it shows up in the supermarket queue, or mid-dream, or while eavesdropping on a toddler in a coffee shop. Capture it. Write it down, scribble it in your phone, record a voice memo.

Half the job of writing for children is staying open, letting the small sparks of an idea grow instead of brushing them off as “silly.”

When people ask for tips for writing a children’s book, they usually expect a checklist. But story ideas aren’t built from checklists. They’re built from noticing. Feeling. Remembering. Imagining.

So don’t sit around waiting for the “perfect” idea. Start with the strange ones. The small ones. The ones that make you grin or tear up for reasons you don’t fully understand.

That’s where the real stuff lives.

Outline a Simple but Engaging Structure

There’s a dangerous myth that floats around in the world of writing children’s books: that kids don’t care about structure. That because they’re small, you don’t need to worry about things like plot, pacing, or resolution.

Don’t buy it.

If anything, structure matters more in kids’ books. Why? Because attention spans are short. Because kids don’t have time for scenes that wander or characters who waffle. Because a child instinctively knows when a story is dragging, even if they don’t have the words to explain why they’re suddenly squirming in their seat or reaching for a snack instead.

So let’s talk about the steps to writing a children’s book that keeps a kid hooked, all the way from page one to “again, again!”

Start with the Basics: Beginning → Middle → End

You’ve heard this before, but it’s worth repeating. Every solid children’s story has three core movements:

- The Beginning: Introduce your character and their world. Let us know what they want, or what’s missing.

- The Middle: Something goes wrong. There’s a challenge, a surprise, a conflict. This is where the stakes build and the character has to try, fail, try again.

- The End: Resolution. The character changes or grows. Something important is gained, learned, or realized.

That arc, no matter how simple, creates momentum. Kids feel it. They crave it.

Picture Books: Think in Spreads

For picture books, structure gets even more technical. Most are 32 pages, which means 12–14 full spreads (a spread is two facing pages). That means every moment in the story has to earn its space.

Each spread should move the story forward, create anticipation, or offer a satisfying visual beat. Page turns aren’t just about layout, they’re rhythm. Use them to build surprise, humor, and emotional punch.

Use Repetition and Rhythm to Build Momentum

Repetition isn’t lazy, it’s a tool. In fact, it’s one of the most effective ways to give young readers a sense of control and anticipation. Think of books like We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or The Very Hungry Caterpillar. The rhythm pulls kids along and makes them feel like they’re part of the story.

This is especially important in early books, where the music of the language is doing as much work as the plot itself.

Keep It Simple, but Not Shallow

When you’re mapping out your story, don’t overcomplicate things, but don’t underestimate your reader either. Simplicity in structure doesn’t mean you have to water down the emotion. You can still explore big ideas, fear, hope, belonging, within a simple narrative frame.

Great stories for kids hit on something true and human, just in a smaller, sharper package.

So yes, outlining might sound like the “boring” part of writing children’s books, but it’s also where your story becomes readable, re-readable, and unforgettable.

Once you’ve got a solid structure, everything else, character, language, visuals, has something to hold on to.

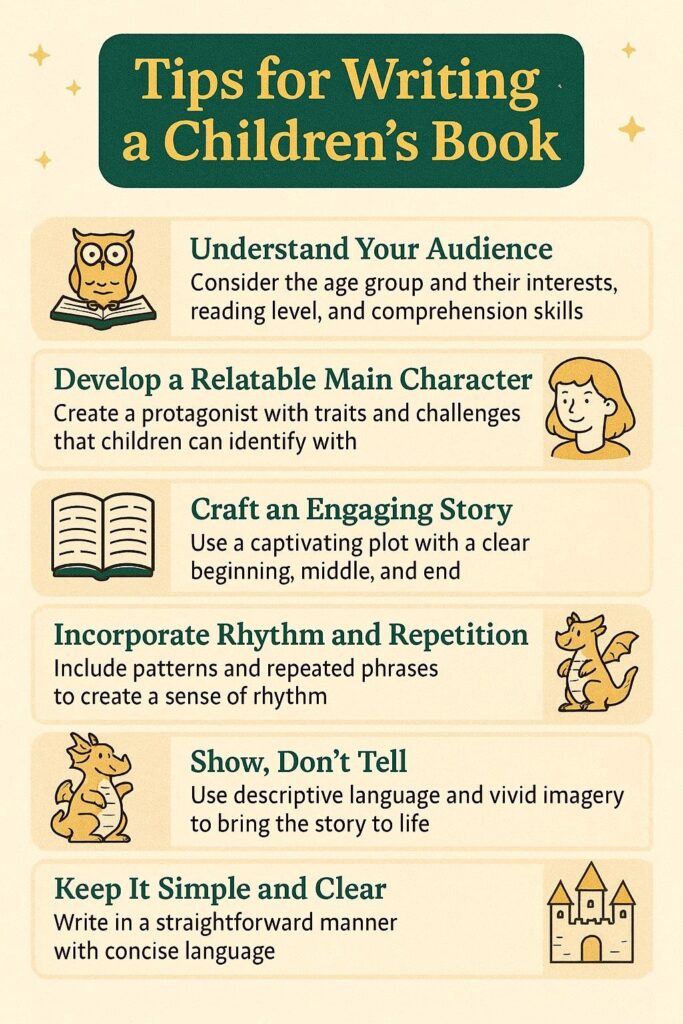

Craft a Child-Centred, Active Protagonist

If there’s one thing that instantly disconnects a child from a story, it’s this: a main character who doesn’t do anything.

Children want heroes, big or small, who act, try, fail, and try again. They want characters they can see themselves in. And if you’re wondering how to start writing children’s books that kids actually care about, start with this: give them a protagonist who matters.

Your main character should be the one making choices. Solving problems. Facing fears. Not Mum. Not Dad. Not some wise old owl giving them advice. Kids want stories where they are the centre of the universe, because that’s how childhood feels.

Make Them Feel Real (Even If They’re a Talking Llama)

Whether you’re writing about a shy dinosaur, a time-travelling toaster, or an ordinary kid who feels invisible at school, your character needs to feel emotionally true.

That means giving them real wants and needs. Maybe they want to fit in. Or feel brave. Or make a friend. Maybe they’re scared of being left out or not being enough.

Children live big feelings in small bodies. Your character should reflect that. Even if your story is silly or fantastical, the emotion has to land.

And here’s the key: the character should grow. They don’t need to “win” or end up perfect. But they should change in some way. That’s what gives a story its heartbeat.

Give Them a Voice Kids Recognize

The voice of your protagonist should sound like a kid, not a mini adult. This doesn’t mean dumbing things down. It means capturing the rhythm and logic of how kids think.

They might ask too many questions. They might misunderstand things. They might jump to wild conclusions. That’s the beauty of it. The more you tap into that worldview, the more a young reader feels seen.

So don’t write how you think kids talk, spend time around them. Listen. Read their books. The difference will show.

Don’t Let the Adults Steal the Show

One of the most overlooked tips for writing a children’s book: keep the grown-ups in the background. It’s tempting to make an adult swoop in and solve the problem, but resist. Even if there’s a parental figure around, your protagonist should be the one taking the reins.

Let them mess up. Let them fix it. Let them own the story.

Because in the end, kids don’t want to be protected from the world, they want to be empowered inside it.

Once your character feels alive on the page, you’re no longer writing at kids. You’re writing for them.

Write in Language That Resonates

Here’s the brutal truth: if a sentence doesn’t sound right out loud, it won’t work for kids. They’ll zone out. They’ll fidget. They’ll start talking to the dog.

And if you’ve ever read a clunky children’s story aloud to a room full of restless kids, you know exactly what I mean.

Rhythm, clarity, and tone matter. In fact, they can make or break your story.

This is one of those areas where children’s books writers either shine, or completely miss the mark.

Read It Aloud. Every Time.

Yes, every draft. Not just the final one.

Reading aloud is the fastest way to catch awkward phrasing, overlong sentences, or rhythm that just doesn’t land. Kids aren’t reading your words quietly in their heads the way adults do. More often than not, someone’s reading your story to them, whether it’s a parent, teacher, or librarian with a very short lunch break.

If it doesn’t roll off the tongue, it won’t fly.

Play with Sound (But Don’t Force It)

Kids love playful language. They love sounds that bounce, twist, and tickle the ear. Repetition, rhyme, alliteration, these aren’t gimmicks. They’re tools. They build memory. They invite participation. They make your story stick.

But here’s the thing: forced rhyme is a death sentence. If it sounds unnatural, clunky, or too clever for its own good, scrap it.

Good rhyme works because it serves the story, not because you’re trying to impress anyone.

Simple Doesn’t Mean Shallow

Your language should be clear, but not lifeless. Vivid, but not overwrought. This isn’t about “dumbing it down”, it’s about sharpening your message until it lands cleanly and memorably.

Instead of saying,

“The creature was tremendously frightening,”

try:

“The monster’s eyes glowed yellow. It grinned. Tommy ran.”

Let the reader see it. Feel it. Use strong nouns and verbs. Cut filler words. Trust kids to get it.

Show, Don’t Preach

Don’t explain what the character is feeling, show us through what they do, say, or how they react. Children are incredibly intuitive. You don’t need to spell everything out.

If you’re wondering what makes writing a children’s book truly work, it’s this: language that doesn’t talk down, but pulls kids in. That respects their intelligence, while meeting them where they are.

And when you get it right? You’ll know. They’ll ask for it again. And again. And again.

Think Visually: Let the Pictures Tell Half the Story

This is where many first-time authors stumble, not because they’re bad writers, but because they forget: in children’s books, the pictures do just as much storytelling as the words.

If you’re working on a picture book, you’re not just writing a story, you’re choreographing a dance between text and illustration. And if you’re thinking through the steps to writing a children’s book, understanding how to leave space for the visuals is absolutely crucial.

Your Words Don’t Have to Do It All

It’s tempting to describe everything: what the character looks like, how they feel, what the setting looks like. But if it can be shown in an illustration, let it go.

Here’s a simple rule of thumb: only write what the illustrations can’t show.

For example, instead of saying:

“Milo was sad. He sat on the floor in his blue pyjamas, crying.”

Say:

“Milo missed Mum.”

Let the illustrator show the tears. The body language. The room. Your job is to give just enough.

Use Page Turns as Story Beats

In picture books, every page turn is an opportunity for surprise, suspense, or punchline. Think of them like cliffhangers, tiny ones. They’re the rhythm of your story. Use them to build anticipation.

If you’re writing a funny book, save the joke’s payoff for the next page. If it’s emotional, give the big moment its own spread. Timing is everything.

Don’t Direct the Illustrator

Unless absolutely necessary, avoid notes like “this character should be wearing a red scarf” or “the background is a zoo.” Let illustrators do their job. They’re visual storytellers. And they often see angles you won’t.

Of course, if a visual detail is vital to the plot, note it, but keep it brief and essential.

Picture the Book in Your Head

Even if you’re not an illustrator, you need to think like one. Imagine how each spread might look. Is there visual variety? Is the pacing working? Are there moments for the art to shine without any words at all?

A powerful picture book feels like a duet. Not a monologue.

One of the most overlooked tips for writing a children’s book is learning when to step aside. Let the art do the heavy lifting when it can. Trust the silence. Trust the pictures.

Because sometimes, what you don’t say is what makes the story unforgettable.

Revise and Gather Feedback

So, you’ve written your story. It’s got rhythm, charm, a childlike voice, and maybe even a talking frog with boundary issues. You’re tempted to call it done.

Don’t.

This is where the real magic happens, not in the first draft, but in what comes after. In children’s books writing, revision isn’t polishing, it’s reshaping, rebuilding, and refining until every word earns its place.

Let It Sit

Before you revise, walk away. Let the story cool off for a few days, or a week. When you come back, you’ll see it with fresh eyes. What felt clever may now feel clunky. What felt emotional might feel flat.

This distance is gold. Use it.

Trim the Fat

Children’s books are short for a reason. Every word matters. If you can cut a sentence and the meaning stays the same, cut it. If a phrase repeats something the art will show, cut it. If it sounds good but doesn’t serve the story, cut it.

Brutal? Yes. Necessary? Absolutely.

Read It Aloud (Again)

Yep, again. And probably again after that. You’re listening for pacing, tone, musicality. Imagine a tired parent reading it at bedtime, will they trip over your sentences, or glide through them? Will a child lean in, or zone out?

Share It with Real Kids

This part is terrifying, but it’s the truth-teller. Read your story to a child, or better, a group of kids. Watch what happens. Do they laugh? Do they interrupt with questions? Do their eyes drift halfway through?

Children won’t lie to you. Their bodies will tell you everything you need to know.

Join a Critique Group

There are entire communities out there just for children’s writers, SCBWI (Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators), KidLit411, and local workshops. These groups can offer encouragement, fresh perspective, and very real feedback.

They’ll also help you toughen up. Because not every note will feel good, but many of them will be right.

Revision is where your story becomes a book. Where it stops being “an idea” and starts standing on its own two feet. It’s not the glamorous part of writing children’s books, but it’s what separates a cute draft from a truly publishable story.

Explore Your Publishing Options

So, your story’s solid. The words are tight, the rhythm flows, kids have laughed, or gasped, or asked for more. Now comes the part that feels less creative, more mysterious: getting it out into the world.

There’s no single “right” path here. Just different doors, and each one opens into a different kind of journey. Before you choose, you need to know what matters most to you, creative freedom, control, visibility, support?

Let’s break it down.

Traditional Publishing

This is the more recognized path, especially if you’re hoping to be stocked in bookstores or libraries, or if you dream of working with a well-known publisher. Here’s how it works:

- You submit your manuscript without illustrations (unless you’re a professional illustrator too). Publishers choose the illustrator after accepting your text.

- You’ll likely need to query agents first, as most big publishers don’t accept unagented submissions.

- Expect to wait. Months. Maybe more. It’s competitive, and responses are slow.

- But if accepted? You’ll have a professional editor, illustrator, marketing support, and the credibility that comes with being traditionally published.

Just remember, your control is limited. The publisher may change your title, pair you with an illustrator you didn’t imagine, and shape the final book in ways you didn’t expect.

If you need a professional children’s book editor, contact us.

Self-Publishing

If you want full creative control, quicker timelines, or have a niche story traditional publishers might pass on, self-publishing services is a powerful option.

- You hire the illustrator, editor, and book designer.

- You manage the production, formatting, and marketing.

- You keep more royalties, but you invest more upfront (both time and money).

This path gives you freedom, but demands hustle. It’s ideal for those who have a clear vision, are willing to learn the business side, and don’t mind being their own publisher, promoter, and publicist.

Many successful authors started this way, and some eventually caught the attention of traditional houses later on.

No matter which route you choose, one of the best tips for writing a children’s book is this: learn the business, not just the craft. Publishing isn’t just about art, it’s about positioning. The more you understand the industry, the better equipped you’ll be to make smart, lasting choices for your work.

Keep Growing as a Writer

Here’s the truth no one tells you at the beginning: your first children’s book probably won’t be the one that gets published. And that’s okay. In fact, it’s good.

Because writing isn’t about getting it right the first time, it’s about getting better every time.

If you’re serious about becoming a children’s author, growth isn’t optional, it’s the job.

Build Your Author Identity Early

You don’t need a published book to start showing up like a writer. Create a simple author website. Write a short bio. Share what you’re working on. This isn’t about fake-it-till-you-make-it, it’s about owning your path.

If someone Googles you after reading your manuscript, give them something to find. A quiet online presence can go a long way toward looking like a pro.

Keep Learning the Craft

Attend workshops. Take classes. Watch webinars. Follow editors and authors who talk about the process. The children’s writing community is generous, take advantage of it.

And don’t just read craft books, read children’s books. Hundreds of them. Study what works. Why do certain books get re-read to death while others disappear?

When you’re asking how to start writing children’s books, the answer is almost always: read more, write more, and pay attention.

Build Your Body of Work

Don’t stop after one manuscript. Keep going. Write bad drafts, strange ideas, short stories, long ones. Experiment. The more you write, the more you’ll find your voice, and your stories will get stronger, faster.

Your first story is you learning the piano. Your tenth might be the one that sings.

Connect with the Community

Writing doesn’t have to be lonely. Join critique groups, attend SCBWI conferences, find your people. When you’re around others who get it, it becomes easier to stay motivated and keep going when the doubt creeps in (and it will).

This isn’t a quick game. But if you keep showing up, learning, revising, and connecting, you will grow. You will improve.

And one day, a kid will read your book, hug it to their chest, and call it their favorite.

That’s worth everything.

Rookie Mistakes That Can Sink Your Story (Before It Even Starts)

It’s easy to get swept up in the excitement of a new story idea. You jump in, type like a maniac, and before you know it, you’ve got a first draft. But here’s the thing: enthusiasm without direction often leads to avoidable missteps.

If you’re serious about getting published, or just creating a book that kids actually want to read, then knowing what not to do is just as important as knowing what to do.

Here are the most common misfires that can sabotage even the most heartfelt story:

Talking Down to Kids

Kids aren’t clueless. They’re just new here. And they deserve stories that respect their intelligence and emotional depth. If your tone feels condescending, they’ll tune out immediately.

Instead of simplifying everything, focus on clarity. Keep language accessible, but never patronizing.

Letting Adults Steal the Show

This is a big one. Your story should revolve around the child character, not their parent, teacher, or quirky grandad with all the answers. Even in fantasy stories, the kid should be solving the problem, making decisions, and learning through experience.

The adult might be there, but they shouldn’t be the hero.

Preaching a Lesson

Stories with a moral can be beautiful, but if your message is too heavy-handed, kids will feel like they’re being lectured. That’s not storytelling, it’s a sermon wrapped in paper.

Instead, let the lesson live inside the story. Show it through the character’s choices and consequences. Let kids feel it, not be told what to think.

Dragging the Pace

Kids won’t wait around for a story to “get good.” Every scene has to earn its spot. If a page is just there to fill space, cut it. If a description slows the momentum, trim it.

In the early steps to writing a children’s book, pacing often gets overlooked, but it’s one of the biggest reasons kids abandon a book halfway through.

Copying What’s Trending

You read a book about a farting dragon that sold millions. Great. Doesn’t mean yours will. Chasing trends often leads to shallow stories. Instead, write what excites you. What you wish you had as a child.

That passion? That’s what connects.

Avoiding these traps won’t guarantee you’ll write the next classic, but it will get you one massive step closer to writing a story that feels honest, fresh, and worth a child’s precious attention.

FAQs

Q1: Do I need an illustrator before submitting to a publisher?

A: No. If you’re submitting to a traditional publisher, especially for picture books, do not hire or submit with an illustrator unless you’re a professional illustrator yourself. Publishers want to pair your manuscript with illustrators they choose and trust. Focus on crafting a strong, well-paced manuscript that leaves room for visual storytelling.

Q2: How do I protect my idea from being stolen?

A: You can’t copyright an idea, only your exact written expression of it. If you’re concerned, you can register your manuscript with the U.S. Copyright Office or keep dated drafts as proof of authorship. But the truth is, most publishers and agents aren’t looking to steal, they’re overwhelmed with original submissions. Reputable people in this industry care more about discovering talent than stealing it.

Q3: What if I’m not a parent, can I still write for children?

A: 100% yes. Some of the most beloved children’s authors aren’t parents. What matters more is empathy, observation, and imagination. Spend time with kids in natural settings, schools, libraries, storytimes, and really listen to them. Read widely in the genre. Tune into how kids talk, what excites them, what makes them stop and think.

Q4: How do I know if my children’s book is any good?

A: Test it. Read it aloud. Share it with kids and watch how they respond, are they engaged? Do they laugh, ask questions, lean in? Get feedback from critique groups or a children’s book editor. Also, compare your story to published books for the same age group. Does it feel fresh? Is the language tight? Is the structure solid? Trust your gut, but back it up with feedback.

Q5: What’s the most common beginner mistake?

A: Writing from an adult’s point of view. You might not even realize you’re doing it, it shows up in passive child characters, overly advanced vocabulary, or moral-heavy endings. Kids want agency. They want stories that honor their perspective, not stories that explain the world to them.

Final Thoughts

Writing for children is a craft that demands heart, precision, and a whole lot of listening. It’s not just about cute characters or rhyming lines, it’s about seeing the world through a child’s eyes and telling stories that matter to them.

Whether you’re just starting out or deep in revision mode, keep showing up. Keep learning. And most of all, keep writing stories that spark joy, curiosity, and connection.

If you remember nothing else, let it be this: the best tips for writing a children’s book always come back to empathy, simplicity, and truth.

You’ve got this. If you need to hire a children’s book ghostwriter, feel free to get in touch.