Introduction

You can write a good book and still lose readers. Not because your idea is weak, but because the manuscript was not fully shaped before it met the world.

Stop me if you have heard this one before. You have reread your draft a dozen times, fixed the obvious typos, maybe even shared it with a friend, and now people keep saying it feels “almost there.” That frustration is not about talent. It is about process.

Editing is not punishment for bad writing. It is how good writing becomes trustworthy writing. When the right steps are skipped or done out of order, you do not just risk a few rough sentences. You risk confusing readers, weakening your message, and paying far more later to fix problems that should have been handled earlier.

In this guide, you will learn the non-negotiable book editing stages, why the order matters more than most writers realize, and how to tell what your manuscript actually needs right now so you can stop guessing and move forward with confidence.

What “Editing” Actually Means (And Why People Mix Up the Terms)

If editing feels confusing, it is not because you are missing something obvious. It is because the word editing gets used as a catch-all for several very different processes. When those processes blur together, writers make expensive decisions too early or skip steps they cannot afford to miss.

Before you hire a professional book editor, you need clean definitions. Otherwise, you cannot ask for the right help.

Editing vs. Revising vs. Proofreading

These are not interchangeable, even though people use them that way.

Editing is about improvement. It focuses on clarity, readability, correctness, and consistency. Editing can happen at multiple depths, from big structural issues to sentence-level precision.

Revising is about change. This is when content is added, removed, reordered, or rewritten. Revising is usually driven by the author, often in response to feedback from developmental editing or early readers.

Proofreading is the final quality check. It happens only after the manuscript is formatted or laid out. Its job is to catch surface errors, not to rethink content or style.

When proofreading is treated like editing, problems slip through. When editing is treated like proofreading, the book feels unfinished even if it is technically clean.

The “Levels” of Editing From Macro to Micro

Editing works best when it moves from large decisions to small ones.

First comes the big picture. Does the story work? Does the argument hold? Does the book deliver what the reader thinks they are buying?

Next comes flow. Do chapters or scenes build logically? Do paragraphs move the reader forward without confusion?

Then comes sentence craft. This is where voice, rhythm, and word choice get sharpened without losing personality.

After that comes correctness. Grammar, punctuation, usage, and consistency are locked down so nothing distracts the reader.

Finally, there are typos and layout errors. These are small, but they matter because they are the last thing standing between the book and its audience.

Developmental editing lives at the top of this hierarchy. Proofreading lives at the bottom. Everything else sits in between. When these levels are respected and handled in order, the manuscript gets stronger instead of just cleaner.

The Non-Negotiable Editing Stages (In the Right Order)

This is where most writers go wrong. Not because they skip editing entirely, but because they do it out of sequence.

Editing is cumulative. Each stage depends on the stability of the one before it. When you jump ahead, you create more work for yourself and for anyone you bring in to help. That is how budgets get blown and timelines quietly double.

Think of your manuscript like a building. You do not paint the walls before the foundation is set. You do not install light fixtures before the wiring is finished. Yet writers do the equivalent all the time when they polish sentences that belong in chapters that are not ready to survive.

A professional editor will almost always push you back to the earliest unresolved stage. Not to be difficult, but because fixing surface-level issues on an unstable draft does not serve you or the reader.

The stages that follow exist for a reason. Each one answers a different question.

Does the book work at all?

Does it work the way the reader expects?

Does the writing carry them forward without friction?

Does anything break trust?

When you respect the order, editing feels purposeful instead of endless. When you ignore it, every round feels like starting over.

Next, we start at the only place that actually makes sense. Before you pay anyone.

Stage 0: Manuscript Cool-Down and Self-Edit (Before You Pay Anyone)

The hardest edit is the one you do alone. It is also the most powerful.

Before feedback. Before contracts. Before invoices. Your manuscript needs distance and a ruthless self-edit. This stage sets the ceiling for every edit that follows.

Why a Break Improves Edits

When you step away, your brain stops filling in gaps that are not on the page. You read what is actually written, not what you meant. That is when logic holes show up. That is when repetition becomes obvious. That is when pacing problems stop hiding behind familiarity.

Even a short break can change what you see. A longer one can change what you are willing to cut.

Distance turns attachment into judgment.

Self-Edit Checklist (Quick, High-Impact)

You are not trying to make the manuscript perfect here. You are trying to make it honest.

Start with structure. Do chapters or scenes earn their place, or are some there because they always were?

Move to clarity. Mark every moment where a reader might stop and reread. Confusion is expensive later.

Then attack redundancy. Repeated ideas, filler phrases, and explanations that say the same thing twice drain momentum fast.

Check continuity next. Names, timelines, facts, and internal logic need to agree with themselves.

Finish with style. Voice, tone, and tense should feel intentional, not accidental.

This stage is not optional. Many professional workflows expect a clean self-edit before any paid work begins. Skipping it does not make editing faster. It makes it noisier and far more expensive.

When this stage is done well, everything that follows becomes sharper, cheaper, and more effective.

Stage 1: Early Feedback (Beta Readers, Critique, or Editorial Assessment)

Before you start fixing the book, you need to understand how it lands.

Early feedback is not about polish. It is about perception. You are testing the reader experience while the manuscript is still flexible enough to change without pain.

What This Stage Is For

This stage answers one core question. What is it like to read your book?

You are looking for patterns, not solutions. Where do readers get bored? Where do they skim? Where do they feel confused, unconvinced, or emotionally detached?

This is the moment where blind spots surface. Not because your readers are experts, but because they are not.

When You Should and Should Not Use It

Early feedback is especially useful if you are a debut author, working in a new genre, or unsure about the structure of the book. It helps you course-correct before investing in deeper edits.

It is not a replacement for professional editing. Reader reactions can tell you where something is wrong, but rarely how to fix it.

Deliverables

At a minimum, you should walk away with clear notes and recurring themes from your readers. Beta questions and structured feedback forms help keep responses useful instead of vague.

Some writers choose a professional manuscript critique at this stage. This provides a high-level evaluation and roadmap without diving into sentence-level edits. It can be especially helpful if you feel stuck and need clarity on what the book actually needs next.

This stage gives you direction. The next stage gives you solutions.

Stage 2: Developmental Editing (Structural and Substantive)

This is the stage where the book either becomes what it promised or quietly fails.

Developmental editing does not care about pretty sentences. It cares about whether the book works. Fully. Coherently. For the reader you say you wrote it for.

If Stage 1 tells you where readers struggled, this stage explains why and what to do about it.

What This Stage Fixes (The Architecture)

At this level, nothing is sacred. Everything is examinable.

For fiction, the focus is on structure and momentum. Plot arcs need to hold. Pacing has to serve tension. Point of view must stay controlled. Characters need clear motivation, believable decisions, and stakes that escalate instead of stall. Scenes should turn, not loop.

For nonfiction, the lens shifts but the standard stays high. The book must deliver on its promise to the reader. The structure needs to support the argument. Ideas should build instead of repeat. Gaps get exposed. Redundancy gets trimmed. The audience is constantly kept in view.

This is not about taste. It is about function.

What You Receive

Most developmental edits come with a detailed editorial letter. This letter breaks down what is working, what is not, and where the manuscript is losing power or clarity. It often includes chapter-by-chapter or section-level notes.

Some editors also provide an annotated manuscript with high-level comments to illustrate issues directly in context. The goal is understanding, not just instruction.

You are expected to revise after this stage. Substantially.

The Rule You Do Not Break

Developmental editing comes before line editing and copyediting. Always.

If you skip this step or rush through it, every later edit becomes fragile. You end up refining prose that sits on unstable ground. That is how books become technically clean but emotionally flat or structurally confusing.

This stage is demanding. It can feel uncomfortable. It can bruise your ego.

It is also the stage that most clearly separates books that hold readers from books that almost do.

Stage 3: Line Editing (Style, Voice, and Flow)

By this point, the structure holds. The book knows what it is. Now the language has to carry the weight.

Line editing lives in the space between meaning and music. It is not about fixing mistakes. It is about removing friction so the reader keeps moving without effort.

This is the stage where many writers finally feel seen, because the work is no longer being taken apart. It is being refined.

What Line Editing Focuses On

Line editing works sentence by sentence, but always in service of the whole.

Clarity comes first. Sentences should say exactly what they mean, no more and no less. Rhythm follows. Variation in sentence length keeps the prose alive. Transitions smooth the handoff from one idea to the next.

Word choice matters here. Repetition gets trimmed. Vague language gets sharpened. Overwritten passages get tightened without flattening your voice.

This is also where tone is aligned. The voice should feel consistent and intentional from beginning to end.

Common Outcomes

After a strong line edit, the manuscript feels lighter. Pages turn faster. Paragraphs breathe. The reader stops noticing the writing and starts noticing the experience.

Nothing flashy. Nothing forced. Just momentum.

When This Stage Is Essential

Line editing is essential when the idea is strong, the structure works, but the writing feels like it is getting in its own way.

Writers often hear feedback like, “I like it, but it did not quite pull me through.” That is the signal.

At this point in the book editing stages, line editing is the difference between competent and compelling.

Stage 4: Copyediting (Correctness and Consistency)

This is the stage that protects your credibility.

By the time a manuscript reaches copyediting, the story or argument should be settled. No more structural shifts. No more stylistic experiments. The job now is to make sure nothing undermines reader trust.

Copyediting is quiet work, but it is unforgiving.

What Copyediting Catches

This stage focuses on correctness at scale.

Grammar, punctuation, spelling, and capitalization are corrected with precision. Consistency is enforced across the entire manuscript. Names stay the same. Hyphenation follows a single logic. Numbers behave consistently. Timelines agree with themselves.

Depending on scope, copyediting may also flag basic factual errors or logic slips. Not to rewrite content, but to prevent avoidable confusion or embarrassment.

Style Guide Choices

Every book needs rules, even if the reader never sees them.

Fiction typically relies on a project-specific style sheet that tracks decisions about spelling, capitalization, and character details. Nonfiction often follows the Chicago Manual of Style, supported by a custom style sheet tailored to the book.

These documents matter because they keep decisions consistent long after memory fails.

Deliverables

A copyedit usually delivers a cleaned manuscript and a detailed style sheet. This becomes the reference point for all future changes.

Within the book editing stages, copyediting is where polish becomes protection. It ensures the reader stays focused on your ideas, not distracted by avoidable errors.

Stage 5: Proofreading (After Formatting and Layout)

Proofreading is the last line of defense. It is not glamorous, but it is essential.

By this point, the manuscript should be fully edited, revised, and formatted. That order matters. Proofreading too early gives a false sense of security and almost always leads to new errors later.

Why Proofreading Is Last

Formatting changes text. Line breaks shift. Spacing adjusts. Words disappear or duplicate themselves in ways no one expects.

This is why proofreading must happen after layout. Not before. Not during.

Proofreading is the final inspection of the book as the reader will see it. Anything missed here ships with the book.

What Proofreaders Look For

Proofreaders scan for surface-level issues only.

Typos. Punctuation slips. Repeated or missing words. Incorrect page numbers. Broken headers. Awkward spacing. Widows and orphans, depending on the format.

They are not rewriting sentences or questioning structure. That work is already done.

The Critical Boundary

Once proofreading begins, major changes stop.

Every new sentence added at this stage risks introducing fresh errors. Even small edits can ripple through layout and undo work you already paid for.

Proofreading is about restraint. You catch what remains, you fix it cleanly, and you let the book go. This stage is not where you make the book better. It is where you make sure nothing breaks it at the finish line.

Optional but Often Smart Add-On Stages (When Your Book Needs Them)

Not every book needs every extra layer. Some do. Knowing when to add support is part of editing well, not over-editing.

These stages sit outside the core pipeline, but they can save you from serious problems later.

Fact-Checking (Nonfiction, Memoir, Business, History)

If your book makes claims, references real people, or presents data, accuracy is not optional.

Fact-checking verifies dates, names, quotations, statistics, and sources. It also helps flag statements that may be misleading or unsupported. This is especially important for nonfiction where credibility is the product.

Sensitivity Reading (When Representation Is Central)

When a book draws on lived experiences outside your own, blind spots are easy to miss.

Sensitivity readers focus on portrayal, context, and impact. The goal is not to sanitize your work. It is to reduce harm, strengthen authenticity, and avoid errors that can break trust with readers you want to reach.

Legal and Permissions Review (Quotes, Lyrics, Claims)

Some risks have nothing to do with craft.

Quoted material, song lyrics, medical or legal claims, and personal stories about identifiable people can create real exposure. A legal or permissions review is not editing, but it can prevent painful problems after publication.

Some writers also choose a manuscript critique at this stage if major revisions have been made and they want a fresh high-level check before moving forward. Used strategically, it can confirm that the book is finally doing what it set out to do.

These add-ons are not about perfection. They are about responsibility.

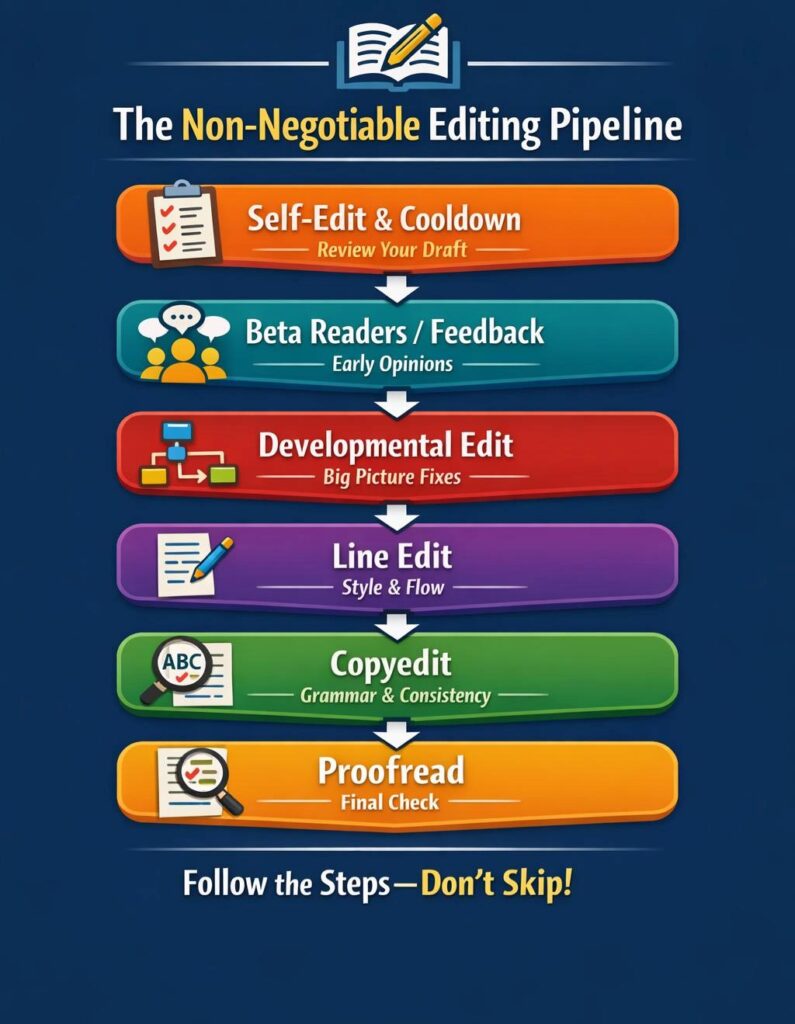

Visual Summary: The Non-Negotiable Editing Pipeline (Quick Order Recap)

When everything starts to blur together, this is the reset. One clean sequence. No shortcuts.

- Self-edit and cooldown

Step away. Come back sharp. Fix what you can before anyone else touches the manuscript. - Beta readers or critique

Gather reader reactions. Look for patterns, not solutions. - Developmental edit

Repair structure, pacing, logic, and reader promise. This is the foundation. - Line edit

Refine voice, flow, and sentence-level clarity so the book carries momentum. - Copyedit

Lock correctness and consistency. Protect reader trust. - Proofread after layout

Catch final errors introduced by formatting. Then stop.

If you ever feel unsure where you are, this list tells you. If an editor recommends jumping backward, that is usually a sign of integrity, not incompetence.

A professional book editor will always respect this order, even when it is uncomfortable, because this pipeline is how books get finished without breaking along the way.

How to Know Which Stage You Need Right Now

Most writers do not need more advice. They need a diagnosis.

When editing feels overwhelming, it is usually because the wrong problem is being solved. This section helps you identify the bottleneck so you can move forward instead of spinning.

Diagnose by Symptoms

The manuscript tells you what it needs if you listen closely.

If the structure feels shaky, chapters drag, or the story does not seem to build, the issue is developmental.

If the ideas are solid but the writing feels wordy, flat, or uneven, line editing is the right focus.

If you are confident in the content but worried about errors, inconsistencies, or professionalism, copyediting is the priority.

If the book is formatted and you are preparing to upload or print, hiring professional proofreading services is the only thing left to do.

Each symptom points to a specific stage. Treating the wrong one wastes time and money.

The Fastest Self-Test (Three Questions)

When in doubt, answer these honestly.

Does the book deliver what the reader thinks they bought?

Do chapters or scenes build logically without confusion?

Is the prose clean enough that errors will not break trust?

If the answer to the first two questions is no, you are not done with structural work. If the answer to the third is no, you are not ready to publish.

Editing gets easier when you stop guessing and start matching the problem to the stage designed to solve it.

Editing Stages for Fiction vs. Nonfiction (What Changes, What Does Not)

At first glance, fiction and nonfiction look like they should follow different rules. Different goals. Different readers. Different pressures.

But the core process does not change. What changes is where the weight falls.

Fiction Emphasis

In fiction, everything bends toward momentum and emotional payoff.

Editors focus heavily on arc, character development, tension, and pacing. Scenes must earn their place. Point of view has to stay controlled. Stakes need to rise in a way that feels both inevitable and surprising.

Language matters, but only after the story works. Beautiful prose cannot save a flat middle or an unconvincing ending.

Nonfiction Emphasis

Nonfiction editing is about trust and clarity.

The structure has to support the promise made to the reader. Arguments need to build logically. Redundancy gets cut aggressively. Gaps get exposed fast. Authority comes from precision and follow-through, not volume.

Actionable takeaways matter. So does respecting the reader’s time.

What Stays Non-Negotiable

No matter the genre, the order stays the same.

Big picture before sentences. Sentences before correctness. Correctness before proof.

The book editing stages still move from macro to micro and end only after layout. When writers try to reverse that order, fiction loses power and nonfiction loses credibility.

Different books. Same discipline.

Traditional Publishing vs. Self-Publishing (Who Covers Which Edits)

The editing stages do not disappear just because you choose one publishing path over another. What changes is who manages them and who pays for them.

Understanding this difference saves you from unrealistic expectations and costly surprises.

Traditional Publishing

In traditional publishing, the publisher typically manages multiple rounds of editing. This often includes developmental editing, line editing, copyediting, and proofreading.

That does not mean the author does nothing.

You are still expected to revise extensively, respond to editorial feedback, and meet deadlines. The process can take longer when working with top book publishing services because it moves through teams, schedules, and internal approvals. You give up speed and some control in exchange for professional infrastructure.

It is also worth noting that not every traditionally published manuscript receives the same depth of editing. The stronger the draft you submit, the better the experience tends to be.

Self-Publishing

In self-publishing, you are the project manager.

That means you decide which stages happen, when they happen, and who does them. It also means you fund them. Nothing is bundled. Nothing is automatic.

The upside is control. You choose the timeline. You choose the editors. You decide how deep to go at each stage.

The downside is responsibility. If a stage is skipped, there is no safety net. The book launches exactly as prepared, for better or worse.

The key truth is simple. The stages do not change. Only the logistics do. Whether a publisher coordinates the process or you do, the work still has to happen for the book to hold up in the hands of readers.

Typical Timelines, Costs, and What Drives Them

Editing rarely takes as long as writers fear. It often takes longer than they plan.

Understanding what affects timelines and costs helps you make smarter decisions instead of rushed ones.

What Affects Cost Most

Word count is the obvious factor, but it is not the only one.

Genre complexity matters. A tightly plotted novel or a research-heavy nonfiction book demands more attention than a straightforward narrative. Draft quality also plays a huge role. A clean, well-structured manuscript costs less to edit than one that needs heavy lifting.

Turnaround speed is another driver. Faster timelines usually mean higher rates, because editors have to reshuffle schedules or work at intensity.

The stage matters too. Developmental work costs more than proofreading for a reason. It requires deeper engagement and judgment.

Why Skipping Stages Gets Expensive

Skipping stages does not eliminate costs. It delays them and compounds them.

When writers line edit before structure is settled, they pay to refine text that later changes or disappears. When they proofread too early, new errors get introduced during revisions, and the work has to be done again.

This is how budgets quietly double.

Editing is cheapest when done in the right order. Each stage reduces risk for the next. When the pipeline is respected, money goes toward progress instead of rework.

The most expensive editing mistake is not hiring help. It is hiring the wrong help at the wrong time.

How to Hire the Right Editor (Without Getting Burned)

Hiring an editor is not a creative decision. It is a business one. The clearer you are going in, the less likely you are to waste money or stall your book.

Start by Identifying the Exact Stage You Need

Before you talk to anyone, be honest about where your manuscript is. Editors are not interchangeable, and no single service fixes every problem.

If the structure is unstable, you need developmental work. If the writing itself is the issue, line editing matters more. If you are worried about errors and consistency, copyediting is the priority. If the book is formatted and ready to release, proofreading is the only stage left.

Knowing this upfront prevents you from buying the wrong service.

Understand What “Full Edit” Really Means

“Full edit” sounds comprehensive. It is also meaningless without detail.

Some editors use it to describe a line and copyedit combined. Others mean a light developmental pass plus sentence-level work. Always ask for a breakdown of what is included and what is not.

Clarity here protects both sides.

What to Ask Before Signing

Do not rely on reputation alone. Ask questions.

Which specific stage are you providing, and how do you define it?

What deliverables will I receive, such as an editorial letter, in-line comments, or a style sheet?

How many passes are included, and is there any follow-up after revisions?

Will you provide a sample edit so I can see how you approach the work?

These answers tell you more than a portfolio ever will.

Evaluate Fit, Not Just Credentials

Credentials matter. Fit matters more.

You should understand the feedback. It should challenge you without condescension. If the editor cannot explain their reasoning clearly, collaboration will be hard.

A good editor does not just mark changes. They teach you how to see your own work more clearly.

What a Good Contract Includes

A professional contract is specific.

It should define scope, timeline, payment schedule, and revision limits. It should address confidentiality and outline what happens if the project is paused or canceled.

Editors who respect the book editing stages will not oversell. They will tell you when you are early, late, or asking for the wrong thing. That kind of honesty is the real green flag.

How to Prep Your Manuscript for Each Stage (So You Do Not Waste Money)

Editors can only work with what you give them. The more prepared your manuscript is for the specific stage you are entering, the more value you get from the edit.

Preparation is not about perfection. It is about alignment.

Before Developmental Editing

At this stage, clarity matters more than polish.

Have a clear sense of who the book is for and what it promises the reader. A short summary of your goals helps an editor evaluate whether the manuscript is delivering.

Prepare a chapter list or outline, even if the book is already drafted. This makes structural issues easier to spot. If you have comparable books or models in mind, note them. Context speeds up insight.

Most important, be open to change. Developmental editing assumes flexibility.

Before Line or Copyediting

This is the moment to stop rearranging the house.

Structure should be locked. Major content decisions should be final. You can still tweak wording, but you should not be adding chapters or cutting large sections.

Clean up obvious issues before you send the manuscript. Fix repeated typos you already know about. Standardize formatting. These small steps keep the editor focused on higher-value work.

Before Proofreading

Everything should be final except error correction.

Formatting must be complete, whether for print or digital. Front matter and back matter should be in place. Page numbers, headings, and spacing should reflect the final version.

Once proofreading begins, restraint matters. Changes should be minimal and necessary. The goal is not to improve the book. It is to release it without avoidable mistakes.

Preparation does not replace editing. It amplifies it. When each stage gets the version it expects, time and money stop leaking out of the process.

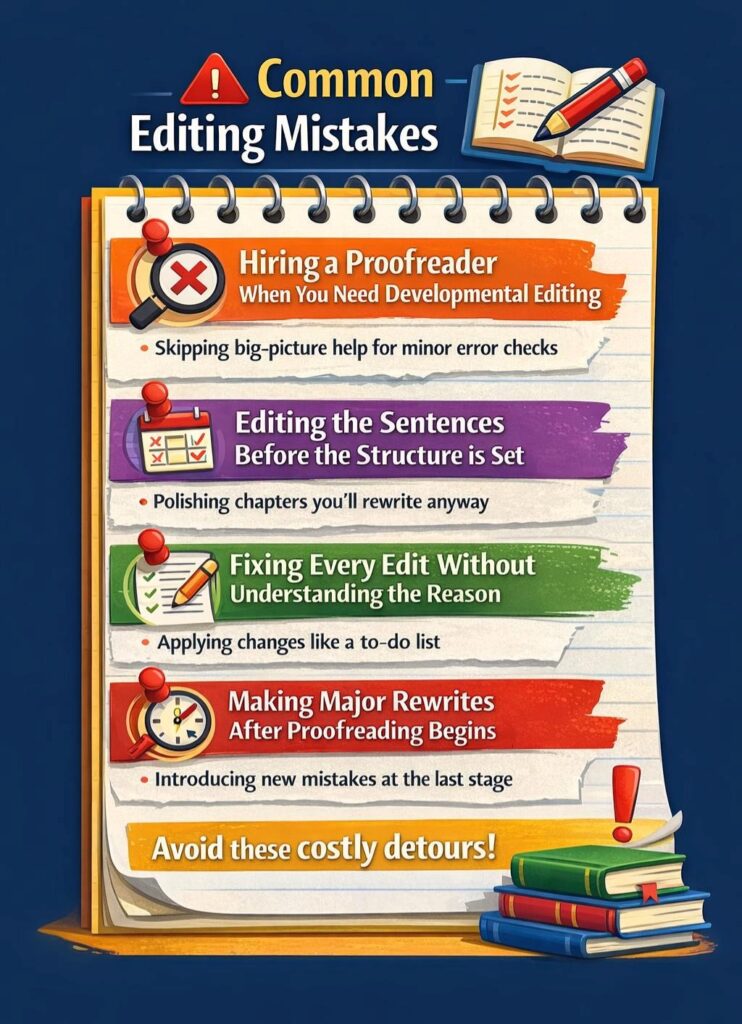

Common Editing Mistakes (That Make Editors’ Jobs Harder)

Most editing problems are not caused by bad writing. They are caused by bad timing.

When stages blur or get skipped, editors end up solving problems the manuscript is not ready to address. That slows everything down and drives up cost.

Hiring the Wrong Edit First

One of the most common mistakes is hiring a proofreader when the manuscript actually needs structural work.

A proofreader can fix surface errors, but they cannot repair pacing, logic, or clarity. The result is a manuscript that looks clean and still does not work. This often leads to frustration on both sides, because the writer feels something is still wrong but cannot pinpoint why.

Copyediting Before the Story or Structure Is Settled

Copyediting too early is a fast way to waste money.

If chapters are still moving, arguments are still shifting, or scenes are still being rewritten, copyediting will have to be redone. Correctness should be locked only after the content is stable. Otherwise, you pay for precision that cannot survive revision.

Accepting or Rejecting Edits Without Understanding Them

Editing is not a checklist to blindly approve or fight against.

When writers accept every change without understanding the reason, they lose control of their voice. When they reject everything out of defensiveness, they miss the point of the edit. The strongest revisions happen when writers engage with the intent behind the feedback.

Making Major Changes After Proofreading Begins

This is the most expensive mistake of all.

Once proofreading starts, the book should be frozen. Large changes at this stage reintroduce errors and undo previous work. Even small edits can ripple through layout and cause new problems.

Expecting One Round to Fix Everything

Another common misconception is believing a single edit will solve all issues.

Most manuscripts need more than one pass, especially at the structural level. Revision and re-evaluation are part of the process. Planning for this reality prevents disappointment and rushed decisions.

Editing works best when each stage does its job and then gets out of the way. Respecting the sequence makes life easier for everyone involved, including you.

FAQs

What Is the Correct Order of Editing a Book?

The correct order is self-editing and cooldown first, followed by early feedback, developmental editing, line editing, copyediting, and finally proofreading after formatting. This sequence protects your time, budget, and reader trust.

Is Line Editing the Same as Copyediting?

No. Line editing focuses on voice, style, clarity, and flow at the sentence level. Copyediting focuses on correctness and consistency, such as grammar, punctuation, capitalization, and internal logic.

Can I Skip Developmental Editing If My Grammar Is Strong?

Strong grammar does not fix structural problems. Developmental issues involve pacing, clarity, argument strength, and reader expectations. A clean sentence cannot rescue a weak foundation.

When Should Proofreading Happen?

Proofreading should happen only after the manuscript has been fully formatted or typeset. Layout changes can introduce new errors, which is why proofreading must be last.

How Many Rounds of Editing Does a Manuscript Usually Need?

Most manuscripts need more than one pass at the macro level, often revision followed by a recheck. After that, micro-level passes like line editing and copyediting are completed, followed by a final proof. The exact number depends on draft quality.

What Is an Editorial Assessment, and Do I Need One?

An editorial assessment is a high-level evaluation that identifies strengths, weaknesses, and next steps without editing the text line by line. It is useful if you are unsure what your book needs or want a roadmap before committing to deeper edits.

Should I Use Beta Readers Before Hiring an Editor?

Often, yes. Beta readers provide valuable reader reaction data that can highlight confusion, boredom, or emotional disconnect. This feedback can help you get more value from professional editing later.

What Editing Stage Is Most Important?

Developmental editing is the foundation because it determines whether the book works at all. Proofreading is the final safety net. Most strong books benefit from the full sequence.

What Is the Difference Between Proofreading and Copyediting?

Copyediting improves correctness and consistency within the manuscript. Proofreading catches final errors after formatting and focuses on surface-level issues only.

Do Nonfiction Books Need Different Editing Stages Than Novels?

The emphasis changes, but the stages and order stay the same. Nonfiction focuses more on structure, clarity, and credibility, while fiction emphasizes arc, character, and pacing.

How Do I Choose the Right Editor for My Genre?

Look for editors with experience in your genre, ask for a sample edit, and confirm they are offering the specific stage you need. Avoid vague services that promise to do everything at once.

Conclusion

Editing is not a judgment on your ability. It is a commitment to your reader.

Every choice you make in the editing process either builds trust or quietly erodes it. When readers feel guided, grounded, and confident in your book, they stay. When they feel confused or distracted, they leave, even if the idea itself is strong.

The reason the process works is not because it is rigid. It works because it is ordered. Each stage answers a different question, and none of them can safely replace the one before it.

You do not need to do everything at once. You do need to do the right thing next.

Identify where your manuscript is right now. Follow the book editing stages in sequence. Resist the urge to jump ahead.

Editing is not about making your book perfect. It is about making it reliable, readable, and worthy of the time your reader gives it.