Introduction

A biography only gets one chance to earn trust. Lose it early, and the reader never fully comes back.

That is what makes biography writing deceptively difficult. You are not just telling a story. You are asking someone to believe you. Every date, every claim, every scene is a quiet test of credibility. When those tests fail, even an extraordinary life starts to feel thin, exaggerated, or unreliable.

Most failed biographies do not collapse because the subject is uninteresting. They fail because of avoidable mistakes. Research shortcuts. Structural drift. A tone that feels biased or unearned. Ethical blind spots that make readers uneasy without knowing exactly why. These problems show up again and again, even for experienced biography writers.

This article breaks down the 17 biography writing mistakes that damage credibility the fastest and shows you how to fix each one. If you want your work to feel grounded, trustworthy, and worth a reader’s time from the first page to the last, this is where you start.

Why Biographies Fail Even When the Subject Is Interesting

Life vs. story

An interesting life does not automatically become an interesting biography. That is the uncomfortable truth many writers discover too late.

A subject can have fame, tragedy, success, and conflict, and still appear dull or confusing on the page. Not because the life lacks substance, but because the writing does. Facts are stacked instead of shaped. Context is assumed instead of explained. The reader is left wondering why any of it matters right now.

Reader effort

Another common failure point is misplaced confidence. Writers assume that if the subject is fascinating, the reader will naturally care. They will not.

Readers expect guidance. They want to understand the stakes, the turning points, and the consequences of decisions. When that guidance is missing, attention fades fast.

Professional gaps

This is also where many biography writing services struggle. They focus heavily on gathering information, interviews, and achievements, but stop short of transforming that material into meaning. The result feels polished but lifeless. Accurate, yet forgettable.

What works

A strong biography does more than report what happened. It reveals patterns. It shows tension. It highlights growth and contradiction. When that narrative layer is missing, even the most fascinating subject can fail to hold interest.

The 4 Failure Zones That Undermine Biography Credibility

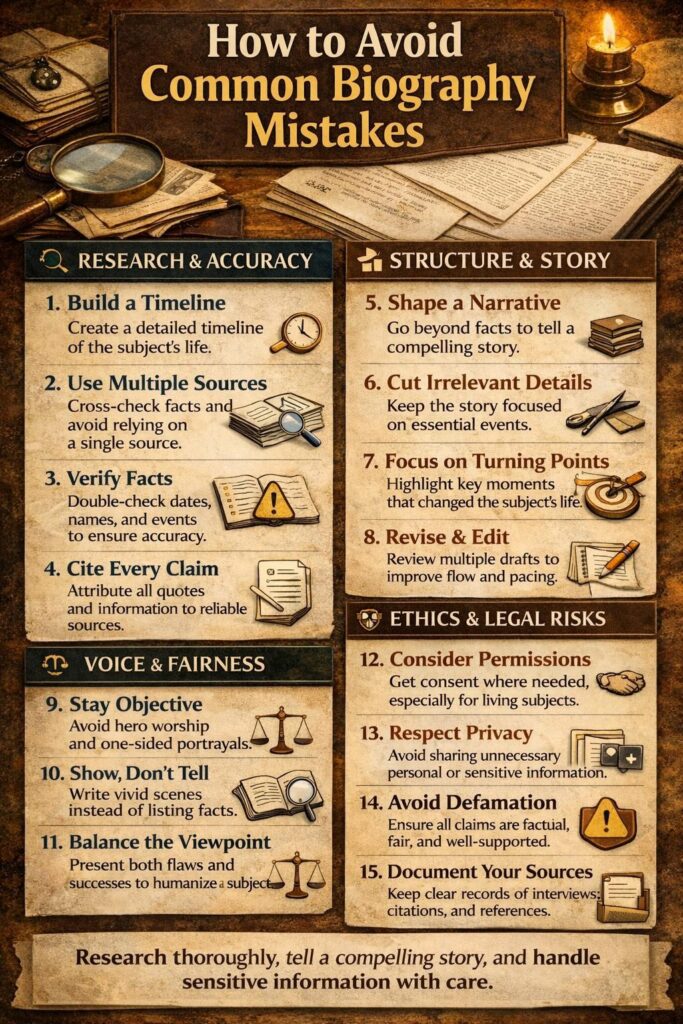

Before going deeper, it helps to see the full landscape. All credibility problems in biography writing fall into four zones, and together they account for all 17 mistakes covered in this guide.

Below is the complete, numbered map so you can clearly see how everything fits.

Accuracy mistakes

- Not getting permission, or not knowing when it matters

- Relying on one source or weak sources

- Failing to build a timeline before drafting

- Starting without a clear scope

- Not defining what kind of biography you are writing

- Getting dates, names, places, or titles wrong

- Making claims without attribution

- Presenting rumors as facts

Accuracy failures are trust killers. Once readers doubt the facts, they doubt everything.

Structure and story mistakes

- Info dumping instead of shaping a narrative

- Poor narrative flow with no clear throughline

- Including irrelevant detail that hurts pacing

- Skipping revision and editing

These mistakes make biographies feel like reference material instead of stories.

Voice and fairness mistakes

- Hero worshiping or portraying the subject as flawless

- Letting bias drive interpretation

- Telling instead of showing, with no scenes or texture

Tone problems are noticed fast. Readers feel them even if they cannot name them.

Legal and ethical mistakes

- Ignoring defamation, privacy, and publicity risks

- Sharing private information without a clear purpose

These mistakes do not just hurt credibility. They can cause real harm.

In the sections that follow, each of these 17 mistakes is broken down with clear explanations and practical fixes so you can avoid them with intention, not guesswork.

Before You Write: The 5 Foundational Mistakes

Most biography problems start before the first paragraph is drafted. Long before voice, pacing, or scenes become an issue, early decisions quietly lock writers into avoidable problems. These mistakes do not look dramatic at the time. They feel harmless. Practical. Easy to postpone.

That is exactly why they are dangerous.

Foundational mistakes shape what information you can access, how reliable your facts will be, and whether your story has a clear direction. Once the draft is underway, fixing these issues becomes expensive in time and credibility. Even experienced biography writers find themselves rewriting entire chapters because something basic was never clarified upfront.

The five mistakes in this section all share one trait. They are preventable. With a small amount of planning, you can avoid research dead ends, structural confusion, and ethical complications before they appear on the page.

Get these right, and the rest of the biography becomes easier to control. Get them wrong, and every later decision becomes harder than it needs to be.

Mistake 1: Not getting permission or not knowing when it matters

Permission is not always legally required, but it often determines access. Public figures and deceased subjects can usually be written about without consent, while private, living individuals often require it. Even when optional, permission can unlock interviews, personal records, and family context that strengthen credibility. The fix is clarity. Decide early whether permission is legally necessary, ethically expected, or strategically useful. Make that decision intentionally, not by default, so access, risk, and research depth are all understood from the start.

Mistake 2: Relying on one source or weak sources

Using a single article or interview creates blind spots and repeats errors. One source equals one perspective, and biographies need more than that. Strong work prioritizes primary sources such as interviews, letters, recordings, and official documents, supported by credible secondary material. The fix is building a simple source ladder before writing. If a claim appears in only one place, treat it cautiously or leave it out until corroborated. Readers may not see your sources, but they feel their reliability.

Mistake 3: Failing to build a timeline before drafting

Without a timeline, contradictions creep in unnoticed. Events drift out of order, cause and effect becomes unclear, and the narrative weakens. A timeline is not just dates. It is a control system that exposes gaps, overlaps, and conflicts in sources. The fix is creating a master timeline before drafting, with source notes attached to each major event. This makes inconsistencies visible early and protects accuracy throughout the biography.

Mistake 4: Starting without a clear scope

When scope is undefined, the biography tries to cover everything and ends up saying nothing clearly. Writers chase side stories, over explain background, and lose focus. The fix is deciding early what the biography is truly about. Choose the time period, theme, and central focus. Cut what does not serve that scope, even if it is interesting. Clear scope gives the biography shape, pacing, and purpose, and prevents endless expansion during drafting.

Mistake 5: Not defining what kind of biography you are writing

Short bios, full biographies, and memoir style narratives follow different rules. Confusing these forms leads to mismatched tone, weak evidence standards, and uneven storytelling. The fix is choosing the form before you write. Define length, audience, voice, and how scenes will be handled. Once the form is clear, decisions about structure, detail, and interpretation become easier and more consistent across the entire biography.

Research and Accuracy Mistakes (The Credibility Killers)

This is where readers start judging you, even if they never say it out loud. Accuracy is the silent contract between you and your audience. Break it once, and everything else becomes suspect.

Research mistakes usually come from pressure. Deadlines. Overconfidence. The belief that small details do not matter. They do. A wrong date, a misattributed quote, an unsupported claim can undo pages of careful storytelling.

This is also where many biography writing services stumble. The focus shifts to speed and volume, and verification becomes a secondary concern. The work may look polished, but polish cannot replace trust.

The next mistakes are not dramatic. They are basic. And they are exactly the ones readers notice first.

Mistake 6: Getting dates, names, places, or titles wrong

Small factual errors cause outsized damage. Readers may forgive stylistic issues, but they do not forgive incorrect basics. A wrong date or misspelled name signals carelessness and invites doubt about everything else. The fix is disciplined cross checking. Verify core facts across multiple independent sources, especially timelines, titles, and locations. Treat basics as sacred. Once trust is lost here, it is almost impossible to rebuild later in the book.

Mistake 7: Making claims without attribution

Unattributed claims weaken credibility fast. Statements like “it is believed” or “many say” leave readers wondering who is speaking and why they should believe it. In narrative nonfiction, attribution still matters, even when citations are not visible on the page. The fix is simple documentation. Track where every major claim comes from using notes, folders, or a spreadsheet. If you cannot trace a claim back to a source, it does not belong.

Mistake 8: Presenting rumors as facts

Rumors are tempting because they add drama, but presenting them as fact damages integrity. Readers can sense when uncertainty is being smuggled in as truth. The fix is responsible labeling. If uncertainty is relevant, clearly state what is known, what is disputed, and why it matters. If a rumor cannot be supported or adds no real insight, omit it. Credibility grows through restraint, not sensationalism.

Structure and Story Mistakes (When It Reads Like a Wikipedia Dump)

This is where many biographies lose readers, even when the research is solid. Facts alone do not create momentum. Without shape, a life story becomes a reference document instead of a narrative.

These mistakes often appear in projects rushed for delivery or handled by a ghost writing company focused more on completeness than coherence. The result is technically correct, yet exhausting to read.

The following mistakes explain why biographies start to feel flat, repetitive, or overwhelming, and how weak structure quietly drains emotional impact and clarity.

Mistake 9: Info dumping instead of shaping a narrative

Listing facts without narrative intent overwhelms readers. Chronology alone is not a story. When events are presented without tension, stakes, or consequence, the biography feels mechanical. The fix is narrative shaping. Decide what each section needs to accomplish emotionally and intellectually. Facts should support a larger arc, not compete for attention. Structure turns information into meaning.

Mistake 10: Poor narrative flow with no throughline

Without a clear throughline, chapters feel disconnected. Readers struggle to understand why one moment follows another. The fix is identifying a central question, theme, or transformation that runs through the entire biography. Every chapter should move that line forward. Flow comes from intention, not chronology alone.

Mistake 11: Including irrelevant detail that hurts pacing

Too much detail slows momentum and dilutes impact. Interesting facts are not automatically useful facts. The fix is a simple filter. Ask whether a detail changes the reader’s understanding of the subject or their choices. If it does not, remove it. Tight pacing strengthens credibility.

Mistake 12: Skipping revision and editing

First drafts expose structure problems. They do not fix them. Biographies often need heavier developmental editing than expected because of their complexity. The fix is planning for multiple revision passes focused on structure, clarity, and balance, not just grammar.

Voice and Fairness Mistakes (Tone Problems Readers Notice Fast)

Voice is where readers decide whether to trust you emotionally. The facts may be solid, the structure clean, but if the tone feels off, the credibility still collapses. Readers sense imbalance quickly, long before they can explain it.

These mistakes are common among new and experienced biography writers alike. They usually come from strong personal feelings about the subject, positive or negative, that slip into interpretation instead of staying grounded in evidence.

The following mistakes explain how tone, bias, and weak scene building quietly undermine even well researched biographies.

Mistake 13: Hero worshiping or portraying the subject as flawless

When a subject is presented as perfect, the story feels false. Real people have contradictions, failures, and blind spots. Removing them drains emotional weight and damages trust. The fix is balance. Show strengths alongside limitations. Let actions and consequences speak for themselves. Credibility grows when readers see a full human being, not a polished symbol.

Mistake 14: Letting bias drive interpretation

Bias turns biography into advocacy or accusation. When interpretation outruns evidence, readers disengage. The fix is separation. Present evidence clearly, add context, and signal where interpretation begins. Allow room for complexity and uncertainty. Readers respect nuance more than certainty.

Mistake 15: Telling instead of showing

Summaries alone flatten a life story. Without scenes, texture, or concrete moments, biographies feel distant. The fix is selective scene building, used only when supported by sources. Dialogue and description must be accurate, not imagined. Showing creates connection, but honesty protects credibility.

Legal and Ethical Mistakes (What Can Get You in Trouble)

This is the section writers often underestimate until something goes wrong. Legal and ethical issues rarely announce themselves while you are drafting. They surface after publication, when stakes are higher and fixes are harder.

Unlike stylistic problems, these mistakes can have consequences beyond credibility. They can damage reputations, strain relationships, or trigger legal action. Even well intentioned writing can cross lines if boundaries are not clearly understood.

The final two mistakes focus on risk, responsibility, and judgment. They are not about fear. They are about writing with care, purpose, and respect for real people whose lives do not end on the page.

Mistake 16: Ignoring defamation, privacy, and publicity risks

Writing about real people, especially living ones, carries legal risk. Defamation claims arise when false statements harm reputation. Privacy issues appear when personal details are shared without justification. Publicity rights can be triggered when a person’s identity is used commercially. The fix is awareness. Understand basic legal boundaries, assess risk before publishing, and document sources carefully. When in doubt, get legal guidance before release.

Mistake 17: Sharing private information without a clear purpose

Including private details simply because they are available is an ethical failure. Readers sense when harm outweighs value. The fix is a simple test. Is the information necessary to understand the subject? Does it serve public interest? Does it minimize harm? If not, remove it. Ethical restraint strengthens trust more than disclosure ever will.

Common “Quick Bio” Mistakes (If the Reader Means a Short Biography)

Short biographies look simple, but they fail fast when written carelessly. Because space is limited, every sentence carries more weight. There is no room to hide weak choices.

Many biography writers underestimate how different short bios are from long form work. They default to lists of roles, dates, and achievements, hoping volume will signal credibility. It does not.

The most common quick bio mistakes come from misunderstanding purpose. A short bio is not meant to capture an entire life. It exists to orient a specific audience, in a specific context, with a specific goal in mind. When that focus is missing, even a short biography becomes forgettable.

Mistake 18: Being generic or list like

Quick bios often read like bullet points turned into sentences. Titles, dates, and roles are stacked without context or meaning. The fix is specificity. Choose a few details that signal why this person matters to the reader right now. Replace long lists with sharp, relevant framing.

Mistake 19: Writing for yourself instead of the audience

Writers include details they personally value instead of what the audience needs. The fix is clarity. Identify who will read the bio and what they need to understand quickly. Let audience relevance guide every sentence.

Mistake 20: Overselling or adding fluff accomplishments

Exaggeration and vague praise reduce trust. The fix is restraint. Use concrete achievements and plain language. Let facts speak without hype.

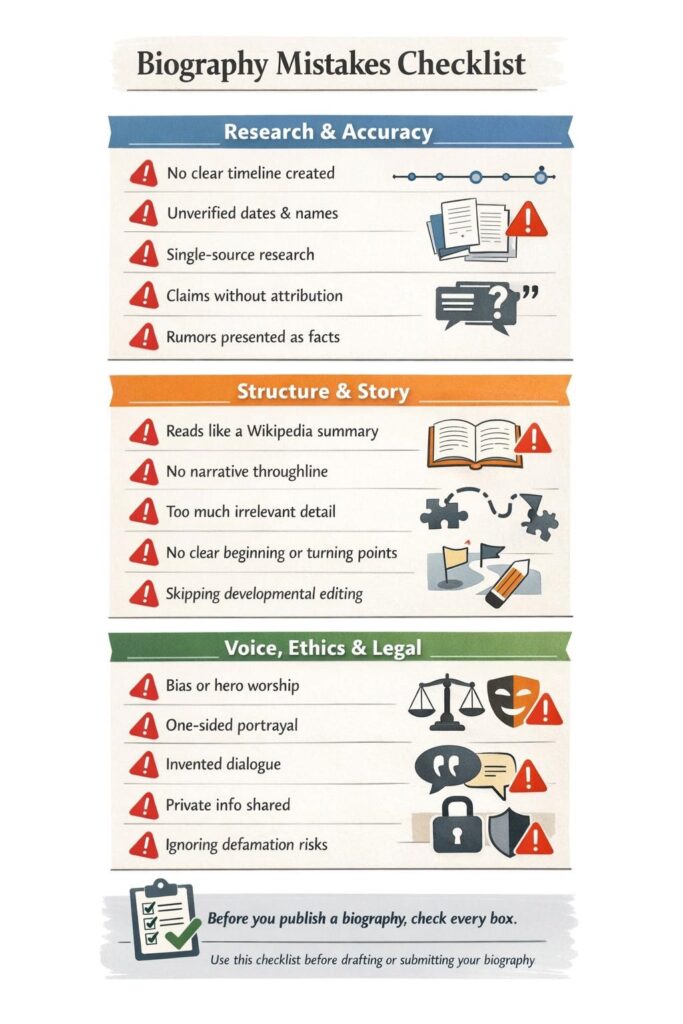

A Simple Biography Mistakes Checklist

Use this checklist before you submit, publish, or hand off a biography. It is designed to catch the problems readers notice first and forgive last.

Research checks

- A complete timeline exists and events appear in the correct order

- Multiple sources support all major claims

- Conflicting information is acknowledged or resolved

- Quotes are accurate and traceable

- Gaps or uncertainties are clearly identified

Writing checks

- A clear throughline guides the entire biography

- Pacing feels intentional, not rushed or bloated

- Scenes are used selectively and supported by sources

- Tone feels balanced and fair

- Interpretation is separated from evidence

Legal and ethical checks

- Permission decisions are intentional and documented

- Privacy boundaries are respected

- Defamation risk has been considered

- Sensitive details serve a clear purpose

- Supporting documentation is saved and organized

A Closer Look at the Biography Mistakes Checklist

A checklist only helps if you understand what each point is actually protecting. Below is why each check matters and what to look for before you consider the biography finished.

Research checks

Timeline exists and is accurate

A complete timeline prevents contradictions and confusion. It ensures events appear in the correct order and that cause and effect make sense to the reader.

Multiple sources support major claims

Single source claims weaken trust. Corroboration shows diligence and reduces the risk of repeating someone else’s error or bias.

Conflicting information is addressed

Ignoring conflicts does not make them disappear. Acknowledging uncertainty signals honesty and strengthens credibility.

Quotes are accurate and traceable

Misquoted dialogue damages trust fast. Every quote should be traceable to a clear source such as an interview, letter, or transcript.

Gaps are identified

Admitting what is unknown is better than filling space with assumptions. Readers respect restraint.

Writing checks

Clear throughline

A throughline helps readers understand why events matter. Without it, the biography feels scattered.

Intentional pacing

Good pacing keeps attention. Too slow feels indulgent. Too fast feels careless.

Scenes are supported

Scenes should be built only when evidence allows. Unsupported scenes feel fictional, even when intentions are honest.

Balanced tone

Fairness matters more than praise or criticism. Readers trust writers who show complexity.

Evidence separated from interpretation

Let facts stand clearly before analysis. This helps readers form their own conclusions.

Legal and ethical checks

Permission decisions documented

Clear records protect you later, especially when writing about living subjects.

Privacy respected

Not all true information is necessary. Purpose matters.

Defamation risk considered

Statements about real people must be accurate, supported, and responsibly framed.

Sensitive details justified

If a detail causes harm, it must clearly serve understanding or public interest.

Documentation organized

Good records protect credibility and reduce risk if questions arise later.

If this checklist feels overwhelming, that is a sign you are taking the work seriously. Many writers choose to hire professional biography editors at this stage to stress test accuracy, structure, tone, and risk before publication. That extra layer often makes the difference between a biography that survives scrutiny and one that quietly loses trust.

FAQs

1. What is the most common mistake in writing a biography?

The most common mistake is inaccurate or weakly sourced information. Errors in dates, names, or claims damage trust immediately, and once credibility is lost, readers question everything that follows.

2. Do I need permission to write a biography about someone?

Not always. Public figures and deceased subjects can usually be written about without permission. That said, permission often improves access to interviews and private materials and reduces ethical and legal friction.

3. How do I avoid bias in a biography?

Use multiple sources, provide context, and clearly separate evidence from interpretation. Present facts first, then explain what they may suggest, without forcing the reader toward a single conclusion.

4. Can I recreate dialogue in a biography?

Only if it is supported by reliable sources such as interviews, letters, transcripts, or recordings. If dialogue cannot be verified, summarize the exchange instead of recreating it.

5. What legal risks should I worry about when writing about real people?

Defamation, privacy, and publicity rights are the most common risks, especially when writing about living individuals. Accuracy, documentation, and restraint are essential.

6. How do I keep a biography from feeling boring?

Avoid stacking facts. Build a clear narrative throughline, focus on turning points, and show consequences. Story shape matters as much as information.

7. What is the difference between a biography and a memoir?

A biography is written by someone else about a person’s life and aims for objectivity and verification. A memoir is written by the subject and focuses on personal experience around a specific theme.

Conclusion

A good biography does not begin with style. It begins with trust. Accuracy earns it. Structure keeps it. Fairness protects it. Story rewards it.

This is what separates forgettable life summaries from work readers believe and remember. Every choice you make, from early research decisions to the final edit, signals whether you respect the subject and the reader. When credibility is solid, readers relax. They lean in. They follow the story.

For biography writers, this is the real goal. Not to impress. Not to dramatize. But to tell a life honestly, clearly, and with enough care that the reader never questions why they should keep turning the page.

If you want help structuring your biography or pressure testing it for credibility, now is the right time to do it.