Discover how editing transforms raw drafts into powerful stories. This guide reveals a practical editing workflow; cooling-off read to final proofread, showing how each stage strengthens plot, voice, and emotional impact in both fiction and memoir.

Introduction

You finish the draft. It feels like a triumph: pages upon pages, your characters alive, your memories stitched into scenes. And then the unease creeps in. Something doesn’t flow. A scene that once thrilled you now drags. Dialogue sounds wooden. You wonder if you have written a story or just noise.

This is where editing begins. Not the pedantic red pen of school essays, but the stage where story becomes architecture. Editing is where you pull apart the walls, check the foundations, and decide which rooms stay, which merge, which must be torn down for the whole house to stand tall.

Think of it this way: grammar and typos are the surface polish, but editing in storytelling is the deep work. It is where you ask: does this arc hold tension? Does the theme actually land? Will a reader feel the heartbeat I meant to write? Revision is not just about fixing. It is about aiming.

And that is the beauty of it. Editing does not shrink your story; it sharpens it until every choice, every scene, every line carries weight.

What “Editing” Actually Means (Stages & Scope)

When most writers hear the word “editing,” their minds leap straight to grammar corrections. Commas, spelling, typos. And yes, that work matters. Nobody wants a book full of mistakes. But if that is all you think editing is, you are missing the heart of the craft. The truth is that editing is layered, precise, and powerful. It is the part of the process that turns a promising draft into a story that readers cannot put down.

Editing is not a single stage. It is a journey that starts big and gradually narrows until your sentences gleam. At each stage, you are asking different questions of the manuscript. Am I telling the right story? Does the pacing work? Are my sentences alive or flat? Every layer of revision serves a purpose, and together they build the experience your reader will have.

Let us walk through the main stages of editing in storytelling, because each one does a very different job.

Developmental editing (also called structural editing)

This is the deep-dive stage. Here, the editor looks at the skeleton of the story. Does the premise make sense? Are the stakes high enough to hold attention? Do scenes follow a logical order? In fiction, this might mean rebalancing acts, cutting a subplot, or rewriting a character arc so it drives the narrative. In memoir, it could mean selecting a theme that becomes the “spine” of the book, shaping which memories belong and which ones distract. Developmental editing is about clarity of vision. Without it, a manuscript can feel scattered or hollow, even if the sentences sparkle.

Line editing

If developmental editing is the blueprint, line editing is the music of the language itself. Here the focus shifts to paragraphs and sentences. An editor will look at voice, rhythm, imagery, tone, and emotional resonance. A sentence may be technically correct but emotionally flat. Line editing tunes the writing until it sings. This is where metaphors sharpen, dialogue tightens, and the story begins to sound like itself.

Copyediting and proofreading

These are often confused, but they are not the same thing. Copyediting ensures consistency, accuracy, and correctness across the manuscript. Are character names spelled the same way throughout? Is the timeline clear? Are grammar rules respected? Proofreading comes last, once the book has been laid out for print or ebook. It catches typos, formatting glitches, and the tiny details that can distract a reader.

Together, these layers explain why many writers turn to professional book editing services. An outside editor does more than fix mistakes. They provide distance, objectivity, and expertise. They can see gaps you are too close to notice and patterns you are too attached to break. This does not mean handing your book over to be rewritten. It means collaborating with someone who can help you shape the story you meant to tell all along.

Editing is architecture, music, and polish all in one. Each stage has its own discipline, and together they transform raw draft into story. Once you understand what editing actually means, you can approach the process with purpose instead of dread. You are not just cleaning up words. You are crafting an experience.

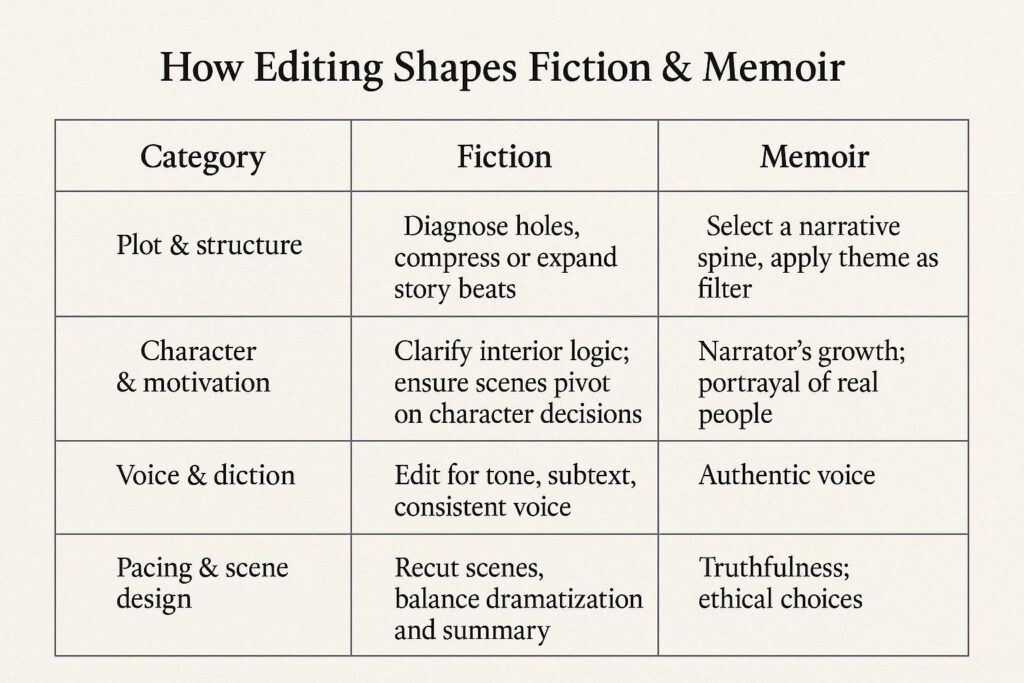

How Editing Shapes Fiction

Editing is not a cosmetic touch for fiction. It is surgery, architecture, and music all at once. A novel rarely emerges ready-made; it is shaped draft by draft, decision by decision. Let us look at how editing reshapes the essential parts of fiction.

Plot and Structure

Stories live or die on structure. A shaky beginning, a sagging middle, or a rushed ending can drain power from even the most imaginative premise. During editing, you zoom out and examine the spine of the story. Are acts balanced? Do beats land in the right order? Is there tension pulling the reader forward?

An editor may suggest compressing scenes that wander, expanding moments that deserve more weight, or even cutting entire subplots. This is not cruelty. It is rescue. Structure is the invisible current that pulls the reader through the story. When it works, readers barely notice it. When it fails, they put the book down.

Character, Motivation, and Agency

Readers will forgive many flaws in a story, but they will not forgive cardboard characters. Editing sharpens character motivation and ensures that choices drive the plot. Is your protagonist reactive or active? Do their decisions cause ripple effects?

An editor will press on the interior logic of characters. Why did she run instead of fight? Why did he confess in chapter seven but stay silent in chapter ten? If these choices feel hollow, the story falters. In revision, scenes are recut so that characters always move the story forward.

Voice, Diction, and Line-Level Music

Beyond plot and character lies the soul of a novel: its voice. Line editing focuses on diction, rhythm, and subtext. A sentence can deliver information, or it can sing with tone and resonance.

Editing here is not about correctness but about authenticity. Does the prose sound like this book and no other? Is the imagery precise or vague? Does dialogue hum with subtext or lie flat like exposition? This is where novels are tuned to sound alive.

Pacing and Scene Design

Momentum is everything. Too much summary and a novel drags. Too much dramatization and readers drown in detail. Editing shapes pacing by deciding which scenes deserve full expansion and which can be skimmed or cut.

Scene design is part of this. Does each scene pivot around change? Something must shift, whether it is an action, a decision, or an emotional turn. Editors test each moment with a simple question: what is different at the end of this scene compared to the start? If nothing changes, the scene is not pulling its weight.

Bringing It Together

Plot, character, voice, and pacing are not separate silos. They overlap and reinforce one another. That is why effective revision relies on fiction editing techniques that work across levels, from reordering acts to polishing a single metaphor. Each stage of editing makes the novel more coherent, more alive, and more urgent to read.

Fiction is invention, but invention without editing is chaos. It is only through this shaping that your story becomes what you meant it to be: not just words on a page, but a lived experience for the reader.

How Editing Shapes Memoir (Truth, Theme, and Ethics)

Editing memoir is not the same as editing fiction. Fiction invents worlds, while memoir sifts through real life, selecting and shaping memories until they form a story worth telling. The process requires not only craft but also care, because the stakes are personal. Your memories, your relationships, and sometimes even your safety are on the page. Let us look at how editing transforms lived experience into narrative art.

Selecting a Narrative Spine

Life is messy. A memoir cannot include everything, and if it tries, it will collapse under its own weight. The first task of editing is to find the spine: the theme or question that gives the story focus. Are you writing about resilience, about forgiveness, about the way family patterns echo through generations? Once the spine is chosen, you can sort memories into what belongs and what does not. This is the shift from a life-everything to a story-about-something.

Balancing Scene and Reflection

Memoir is more than a diary of events. Readers need both the immediacy of lived moments and the reflection that gives them meaning. Editing balances these modes. Too much scene, and the book feels like raw footage. Too much reflection, and it feels like an essay detached from life. Editors tune the rhythm so that readers move between experience and insight, feeling the event and then understanding why it matters.

Memory, Accuracy, and Ethical Choices

No one remembers everything perfectly. Dialogue is reconstructed, events blur, details fade. Editing a memoir means facing these gaps honestly. Should you compress several people into a composite character? Should you change names to protect privacy? What do you do when family members dispute your version of events? These are not just stylistic decisions but ethical ones. The goal is not absolute accuracy, which is impossible, but integrity.

Emotional Honesty vs Self-Protection

One of the hardest parts of editing a memoir is deciding how vulnerable to be. Too guarded, and the story feels flat. Too exposed, and you risk harm to yourself or others. Editors help writers find a middle ground. They push for honesty where it strengthens the story, but they also coach toward careful disclosure when necessary for safety or legal reasons. Memoir editing is not about stripping you bare. It is about telling your truth in a way that connects without destroying.

Craft and Care Together

Memoir is a balancing act between art and responsibility. Structure matters, pacing matters, voice matters. But so does the handling of memory and ethics. The best memoir editing tips combine both: tools for shaping narrative and sensitivity for navigating the personal cost of telling your story.

Memoir is not simply about what happened. It is about why it matters, and editing is the bridge that transforms private memory into a story that resonates with others.

Fiction vs Memoir: What’s Different in the Edit?

Fiction and memoir share tools, but they do not share the same compass. Both need structure, voice, pacing, and clarity, yet the editor’s focus shifts depending on whether the world is invented or drawn from lived experience. Understanding this difference helps you approach revision with sharper intent.

Fiction: Coherence and Causality

In fiction, editing is about coherence. A world, even a fantastical one, must follow its own rules. Characters must act with believable motivation, and events must ripple outward in logical cause and effect. If a subplot distracts from the main arc, it is cut. If pacing lags in the middle, acts are rebalanced. Readers may know the world is made up, but the story still has to feel inevitable.

Editors working in fiction also pay close attention to voice and diction. The goal is immersion. Nothing should jar the reader out of the invented world. This is why many authors seek fiction editing services, because having another set of eyes on your structure and voice can be the difference between a manuscript that feels loose and one that holds a reader’s full attention.

Memoir: Authenticity and Meaning

Memoir is not bound by invented rules but by trust. Readers open a memoir to experience truth filtered through perspective. Editing here focuses on authenticity: does the voice sound honest, or is it hiding behind armor? Are the chosen events serving the theme, or are they simply there because they happened?

Editors help memoirists sift memory into story. They ask: why does this scene matter, and what reflection grows out of it? The work is not only about clarity but about resonance. A memoir succeeds when the personal becomes universal.

The Lens of “Why It Matters”

The most important difference lies in emphasis. Fiction leans on coherence and causality. Memoir leans on verifiability and reflection. Both use the tools of editing in storytelling, but the guiding lens changes. In fiction, the question is, does this world make sense? In memoir, the question is, does this truth connect and carry meaning?

Both forms are demanding. Both require courage. Yet knowing which lens applies helps you accept the kind of cuts, revisions, and reshaping your manuscript will need.

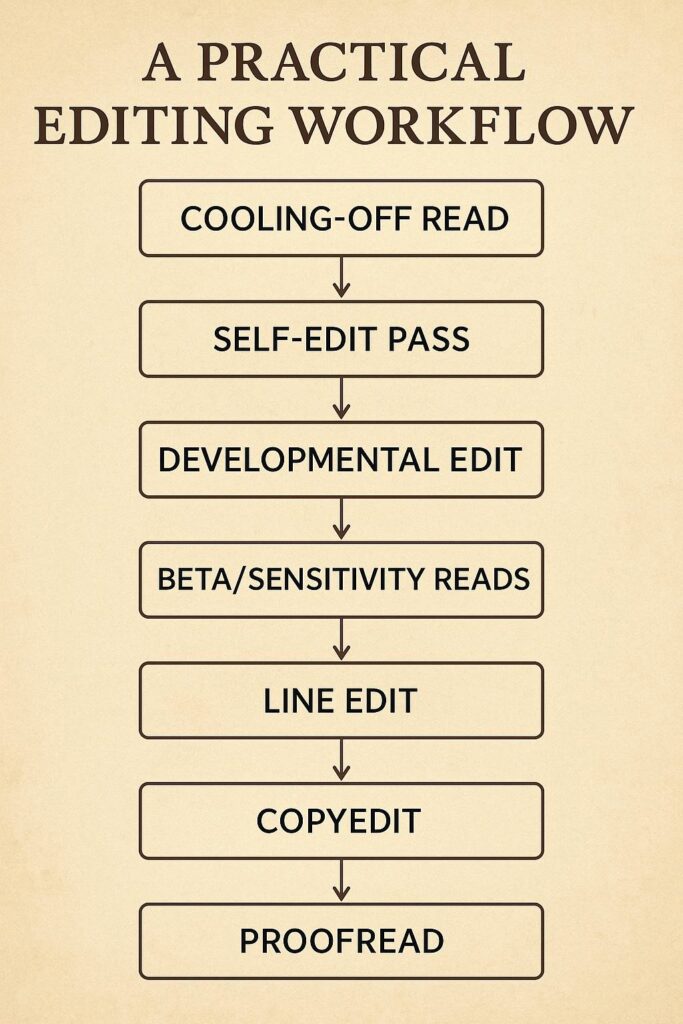

A Practical Editing Workflow (Author + Editor)

Editing can feel overwhelming when you do not know where to begin. Should you polish sentences, or tear apart chapters? Should you fix grammar, or restructure the whole book? The truth is that editing is a layered process, and following a clear workflow can save you from both chaos and burnout. Here is a step-by-step path most writers and editors use.

1. Cooling-Off Read

After finishing a draft, put it away for a while. Distance is essential. When you return, read the manuscript as a stranger would. Do not mark every typo. Instead, jot down broad impressions. Where did you get bored? Where did you feel pulled in? This first re-read is about defining intent. Write a short brief for yourself: what is the theme, what is the story trying to achieve, and who is the reader?

2. Self-Edit Pass (Macro to Micro)

Start with the big picture before zooming in. Look at structure, pacing, character arcs, or thematic focus. Only when those are stable should you move down to paragraphs and sentences. This prevents wasted effort polishing lines that may not survive later cuts.

3. Developmental Edit

At this stage, a professional editor can step in with a full report and margin notes. They will analyze structure, arcs, and narrative clarity. Out of this comes a revision plan, which acts as a map for your next draft.

4. Beta Readers and Sensitivity Reads

Once big revisions are done, trusted readers can highlight blind spots. Beta readers give general impressions, while sensitivity readers are crucial for checking cultural or ethical representation, especially in memoir. For memoirists, this stage may also involve legal review if sensitive details are included.

5. Line Edit and Copyedit

Here the language is tuned. Line editing focuses on rhythm, imagery, and voice. Copyediting ensures consistency, grammar, and accuracy. Together, they refine both art and correctness. This is where fiction editing techniques overlap with memoir editing tools: the pursuit of clarity, flow, and resonance at the sentence level.

6. Proofread After Layout

The final stage happens after design. Once the manuscript is typeset for print or ebook, proofreading catches last-minute glitches, from a missing comma to a formatting slip. It is the last safeguard before your story goes out into the world.

Why Workflow Matters

Editing without structure can feel like chasing shadows. Following a layered process ensures that you are always working on the right problem at the right time. It protects your energy and sharpens your story, no matter whether you are writing fiction or memoir.

Scene-Level Tools That Change Story Outcomes

Big-picture edits shape the spine of a book, but often the real transformation happens at the level of individual scenes. Stories are built moment by moment, and when scenes fail to carry weight, the whole book suffers. Here are tools editors use to test and strengthen scenes.

The Pivotal-Moment Test

Every scene should change something. If nothing is different at the end compared to the beginning, the scene is static. Editing applies this test relentlessly. Did the character make a choice? Did the situation escalate? Did tension rise or release? If not, the scene either needs rewriting or removal.

Cause-and-Effect Chains

Weak middles often come from broken cause-and-effect links. Scenes must flow into one another so that every event feels inevitable. Editors trace these chains: if Chapter Eight could be lifted out without affecting Chapter Nine, the chain is broken. Repairing this restores momentum and makes the story feel alive.

Dialogue Compression

Conversations on the page are not real-life chatter. They must earn their space. Editors cut filler and repetition, leaving only what moves character or plot forward. A tighter exchange is sharper, funnier, and more impactful than a transcript of casual talk.

Image Specificity

Vague description drains energy. “She walked into a room” tells little. “She stepped into a kitchen that smelled of burnt toast and lemon cleaner” anchors the reader in time and place. Editors push for specificity in images, because precision creates immersion.

Why These Tools Matter

Scene-level revision is not a minor polish. It is where emotional energy lives. Whether you are writing fiction or memoir, scenes are the pulse of the book. For memoir in particular, applying these techniques alongside memoir editing tips ensures that personal experiences are not just told but felt by the reader.

Editing scene by scene ensures that your story is more than a sequence of events. It becomes a chain of moments, each one propelling the reader forward.

Common Pitfalls Editors Fix

Every manuscript, no matter how promising, carries blind spots. Writers are too close to their own work to see them clearly, which is why editing is such a powerful tool. Here are some of the most common problems editors encounter and repair.

Backstory Dumps

Dropping an entire life history in one chunk halts narrative flow. Editors spread backstory more naturally, weaving it into scenes where it feels relevant and alive.

Overly Summarized Trauma

In both fiction and memoir, writers often summarize difficult events instead of dramatizing them. Readers need to feel the weight of these moments. Editing helps expand scenes with detail and emotional depth, ensuring the impact is not lost.

Inconsistent Timelines

Stories falter when timelines wobble. Characters age at odd rates, seasons skip, or events overlap illogically. Editors map timelines carefully so the flow of time feels natural and consistent.

Tone Drift

Manuscripts sometimes change tone midstream, shifting from serious to comic without intent. Editing smooths these shifts, aligning tone with theme and genre.

Redundant Beats

Scenes that repeat the same conflict or emotion weaken the story. Editors cut or reshape them so each beat offers new movement or tension.

“Nice but Neutral” Scenes

Some passages are beautifully written but do nothing for the story. Editors test every scene: does it advance plot, reveal character, or deepen theme? If not, it must change or go.

Why Pitfalls Matter

These issues might seem small, but together they can drain the energy from a book. Strong editing turns clutter into clarity. And for memoirists especially, pairing structural fixes with memoir editing tips ensures that personal truth is conveyed with both power and precision.

Choosing the Right Editor (and When)

Not every edit is the same, and not every editor is right for every stage of your book. Knowing when to bring in professional help and how to choose the right partner can save you both frustration and money.

Match Stage to Edit Type

- Early draft: You may only need a manuscript evaluation, a broad overview of strengths and weaknesses.

- Middle draft: This is where developmental or structural editing is most valuable. Big-picture issues are tackled before you sink time into polishing sentences that may be cut.

- Near-final draft: Line editing, copyediting, and proofreading step in to refine voice, ensure correctness, and catch small mistakes.

Trying to skip stages almost always backfires. A polished sentence inside a broken structure is wasted effort.

Questions to Ask an Editor

Before hiring, ask:

- What kind of editing do you specialize in?

- Do you have experience with my genre or form?

- Can you provide a sample edit?

- What does your process look like?

Their answers will tell you whether they are a good fit. The right editor should not only know the craft but also respect your vision.

Sample Edit and Expectations

A short sample edit is invaluable. It shows you the editor’s approach and helps you decide whether their style supports your goals. Be clear about timelines, costs, and the level of feedback you want. Editing is a collaboration, not a takeover.

Special Note for Memoirists

Because memoir involves sensitive truths, family relationships, and sometimes legal risks, it is especially important to choose someone who understands both craft and ethics. Many writers turn to memoir editing services for this reason, seeking editors who can balance narrative clarity with care for personal truth.

The Right Fit Matters

An editor is more than a technician. They are a partner in shaping your story. Choose someone who sees your potential, challenges your blind spots, and believes in the book you are trying to write.

Case Snapshots

Sometimes the most powerful changes in a manuscript are also the simplest. Here are a few quick examples of how editing transforms a story.

- Fiction: An author cut a beloved subplot involving a secondary character. Painful at first, but it freed the protagonist’s arc to breathe and gave the climax sharper focus.

- Memoir: A draft originally followed strict calendar order. Reframing events around a central theme created momentum and resonance, turning a collection of memories into a compelling narrative.

These small glimpses show how editing in storytelling is less about loss and more about uncovering the truest shape of the book.

Tools & Resources

Editing becomes less overwhelming when you have the right tools at hand. Whether you are polishing a novel or refining a memoir, these resources can guide and support you through each stage.

Online Platforms

- Reedsy Guides and Directories: A trusted place to find professional editors, along with detailed articles on every stage of the editing process.

- Editorial Freelancers Association (EFA): A directory of experienced editors where you can search by speciality.

Checklists and Frameworks

- Editing Checklists: Break down tasks into manageable steps, from structural questions like “Does every scene turn?” to surface checks like “Are typos gone?”

- Scene Diagnostic Tools: Useful for testing momentum, character agency, and thematic alignment on a scene-by-scene level.

Books on Craft

- Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Renni Browne and Dave King: A classic resource for understanding revision at both structural and line levels.

- The Artful Edit by Susan Bell: Offers practical strategies for seeing your draft with fresh eyes.

Software Support

- Scrivener: Helps organize large manuscripts, especially when moving scenes or restructuring.

- ProWritingAid / Grammarly: Good for catching surface-level issues, though no substitute for human judgment.

Community and Feedback

- Writing Groups: Peer feedback can highlight blind spots before you bring in a professional.

- Beta Reader Networks: Early readers help test pacing, tone, and clarity from the audience perspective.

The right resource will not replace an editor, but it can give you structure, accountability, and confidence as you refine your manuscript.

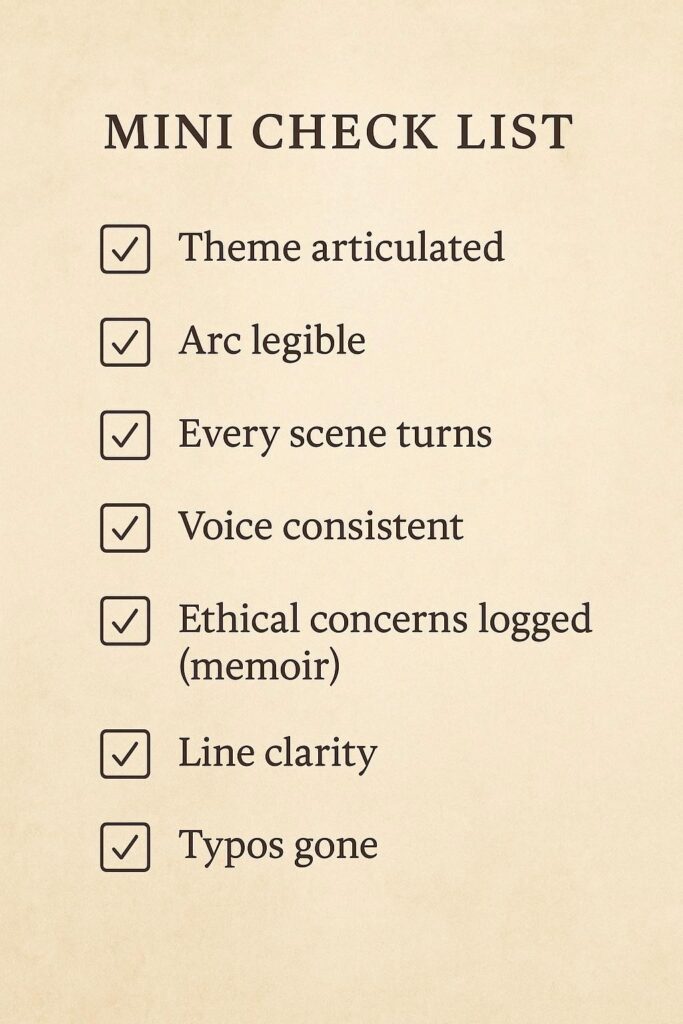

Mini-Checklist: Is My Story Ready for the Next Edit?

Before sending your manuscript to an editor, or even before moving on to the next self-edit pass, ask yourself these questions. They will save you time, money, and stress.

- Theme articulated? Can you clearly state what your book is about beyond plot or memory?

- Arc legible? Does the story have a beginning, middle, and end that feel connected?

- Every scene turns? Does something change in each scene, whether in action, decision, or emotion?

- Voice consistent? Does the prose sound like one unified book rather than shifting styles?

- Ethical concerns logged (memoir)? Have you noted sensitive names, disputed memories, or legal risks?

- Line clarity? Are sentences easy to follow, free of clutter, and alive with rhythm?

- Typos gone? Have you cleared surface distractions before passing the draft on?

If you can tick these boxes, your manuscript is in strong shape for the next editing stage. If not, the checklist shows you exactly where to focus first.

FAQs

Q1: What is the real difference between developmental and line editing?

Developmental editing looks at the big picture: story logic, structure, pacing, and arcs. Line editing zooms in to the sentence level, shaping voice, rhythm, imagery, and clarity.

Q2: How does memoir editing differ from fiction editing?

Memoir must balance narrative drive with factual accuracy, ethical sensitivity, and reflective meaning. Fiction focuses on coherence, causality, and the invented rules of its world.

Q3: Do I need both a line edit and a copyedit?

Yes. A line edit ensures your prose sings with clarity and voice. A copyedit enforces correctness, grammar, and consistency before proofreading.

Q4: Can I restructure my life events out of chronological order in memoir editing?

Absolutely. Many memoirs are arranged by theme rather than strict timeline. The key is to handle time shifts transparently and ethically, so readers trust your choices.

Q5: What does a developmental editor deliver?

Usually a detailed report plus margin notes. The report highlights strengths, weaknesses, and specific recommendations for revision.

Q6: How many rounds of editing should I plan for?

At minimum: self-edit, developmental edit, revision, line edit, copyedit, and proofread. Complex projects may require multiple cycles of developmental or line editing.

Q7: I am on a budget. What should I do first when editing my book?

Invest time in structured self-editing and gather feedback from beta readers. Then, if possible, pay for a manuscript evaluation or a sample developmental edit to get targeted guidance.

Q8: How do editors handle sensitive or disputed memories?

They work with disclosures, careful wording, sometimes legal review. The aim is honesty without harm. In memoir, truth must be balanced with responsibility.

Conclusion

Editing is not a punishment for imperfect drafts. It is the stage where stories are born into their true form. Fiction becomes sharper, more inevitable. Memoir becomes clearer, more resonant. At every level; from the broad sweep of structure to the smallest line edit, editing brings intention, precision, and heart.

If you are staring at your draft and wondering whether it is good enough, remember this: no first draft ever is. What matters is the willingness to refine, to question, and to shape. That is the power of editing in storytelling. It takes the raw material of imagination or memory and transforms it into something that will live in the mind of a reader. Your draft is the beginning. Editing is the path to making it unforgettable.